Maggie O’Farrell

Anything is Possible; Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls

We were spoilt this year by another brilliant and devastating Elizabeth Strout book, hot on the heels of 2016’s My Name Is Lucy Barton. With Anything Is Possible (Viking), Strout turns her clear, incisive gaze on the intricacies and betrayals of small-town life. I’m now dreading the hiatus until the next Strout. Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls (Penguin) has been the definitive book of the year in our house, for both parents and offspring. It offers celebratory, non-judgmental paeans to the varied lives of influential women. Anyone needing an antidote for certain oversexualised, underoccupied screen heroines need look no further.

Sebastian Barry

Smile; Conversations with Friends

A book that made me feel I really was in the presence of a master (and indeed there’s a touch of The Turn of the Screw about it, strangely enough) was Roddy Doyle’s new novel, Smile (Jonathan Cape). In quite another world of experience, but just as Irish for all that, Sally Rooney in Conversations with Friends (Faber) seems to be Truman Capote (with his sharpest scalpel) reborn, with more than a dash of the high intelligence of Elizabeth Bowen.

Jessie Burton

Madame Zero; Anything Is Possible; The Hate U Give; Priestdaddy

I’ve read some brilliant books this year, but a few stand out for me. Fiction-wise, Sarah Hall’s short-story collection, Madame Zero (Faber), was astonishing: humane yet otherworldly, disturbing, sexy and strange. The woman is a genius. Elizabeth Strout graced us with Anything Is Possible (Viking), her follow-up to My Name Is Lucy Barton. I’m addicted to Strout’s compassionate scalpel and in awe of her powers. She makes the small seem majestic. I also adored The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas (Walker), a book full of life and laughter, told through the eyes of a young black girl in inner-city America who testifies against the police after a tragic shooting. In the nonfiction world, I wept with laughter at Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy (Allen Lane), her memoir of growing up with a Catholic priest for a dad. So weird, so wonderful. I just kept reading the passages aloud.

Charlotte Mendelson

Independent People; The Sparsholt Affair; Stranger, Baby

Can’t we talk about all my unread new books? I’m a late adopter; the more I’m told to read something, the longer it dawdles downstairs, waiting for that unquantifiable moment of ripeness. Or the stacks of disappointing fiction, mostly crime, or the few joys, none recent – Halldór Laxness’s Independent People? Elizabeth Strout? No? Fine, then. I’ve just started The Sparsholt Affair (Picador) by Alan Hollinghurst, my favourite living novelist. It had better be good. Emily Berry’s second poetry collection, Stranger, Baby (Faber), is witty, devastating, brilliant.

Mark Haddon

Division Street; Kumukanda; Black Country

For reasons I don’t quite understand, poetry and I have been at odds with one another for a couple of years. I couldn’t bring myself to read an entire collection and I regularly gave up on poems that dared to go over the page. I simply couldn’t see the point. Then, a few weeks ago, I was sent a Red Cross parcel by Chatto & Windus which contained debut collections by three poets and they blew me away: Division Street by Helen Mort, Kumukanda by Kayo Chingonyi, and Black Country by Liz Berry. I have fallen in love with poetry again. Chatto clearly have some kind of secret hotline to my heart.

Lionel Shriver

The Fall Guy; The Dinner Party; Beautiful Animals

You could not go wrong with James Lasdun’s The Fall Guy (Jonathan Cape), a riveting psychological thriller with a protagonist actually as creepy as Ian McEwan’s stalker in Enduring Love, though (at first) more subtle. In Joshua Ferris’s entertaining collection The Dinner Party (Viking), most of the characters are comparatively sane, but no less deliciously ghastly. Lawrence Osborne’s Beautiful Animals (Hogarth) is both impossible to put down and beautifully written: a great combo.

Hilary Mantel

On Balance; Missing Fay

The poem Nativity, if it stood alone, makes Sinead Morrissey’s On Balance (Carcanet) a sweet Christmas choice, but it is only one of a number of thought-provoking poems in her sixth, prize-winning collection. Morrissey floats the reader glimpses of desires unmet, memories still fluid; the stories swim beyond the edge of the page, buoyed up by possibility. Adam Thorpe’s Missing Fay (Cape) is an intricately crafted novel, sharp-eared, current and full of heart, about a lost teenager in a lost England.

Jackie Kay

Kingdom of Gravity; First Time Ever; Days Without End

Nick Makoha’s Kingdom of Gravity (Peepal Tree Press) is a bold and brilliant poetry debut that does not avert its gaze from trauma and atrocity (exploring along the way the brutal rule of Idi Amin and the civil war) and yet is light on its feet and fills you with hope. Peggy’s Seeger’s substantial and absorbing memoir First Time Ever (Faber) is fabulous, taking us back through British folk and reminding us of why we love her songs. Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End (Faber) totally captivated me – the voice is compelling and immersive and tells a story that we don’t get to hear. Barry faces up to the history of the settlers in America and the slaughter of the Sioux during the American civil war. It is a masterpiece; hypnotic and strange, full of its own music.

Cornelia Funke

The Omnivore’s Dilemma; What a Fish Knows

The Omnivore’s Dilemma (Bloomsbury) by Michael Pollan is, like all of his books, wildly entertaining and enlightening, challenging perceptions. For sure, you will never again look at the products in your supermarket in the same way. Or at the fields of a farmer. Numerous books have shown me how utterly ignorant I am about most creatures I share this planet with, but none humbled me more than What a Fish Knows (Oneworld) by Jonathan Balcombe. Many of us have a soft spot for dolphins and whales, but Balcombe makes it embarrassingly clear how absolutely ignorant (and arrogant) we are when it comes to the vast world of our oceans and their inhabitants.

David Nicholls

Priestdaddy; Respectable; The Red Parts; Days Without End

This year I read a series of fantastic memoirs. I loved Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy (Riverhead), in particular the depiction of her father, a gun-toting, guitar-wielding Republican pastor. Written with a poet’s precision, it’s funny, raucous, thoughtful and angry in turn. Lynsey Hanley’s Respectable (Allen Lane) is a sharp, insightful look at social mobility, and Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts (Vintage) is a harrowing but clear-eyed examination of crime’s emotional fallout. As for fiction, I came a little late to Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End (Faber) but it really is an amazing achievement, especially the brilliantly sustained first-person voice. For page after page, I found myself thinking, how does he do this?

William Dalrymple

India Conquered; The Tartan Turban; The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu

I learned a great deal from Jon Wilson’s India Conquered (Simon and Schuster), an admirably concise, balanced and thoughtful look at how British colonialism maimed India, and the sheer wickedness of so much of what we did there. The product of many years of detailed archival research, Wilson’s book is without question the best one-volume history of the Raj currently in print. I also hugely enjoyed John Keay’s The Tartan Turban (Kashi House), about the allegedly half-Aztec, half-Scottish mercenary Alexander Gardner. Minutely researched, wittily written and beautifully produced, it brings back from the dead one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of travel and exploration and stands as one of Keay’s most memorable achievements. Charlie English’s The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu (HarperCollins) tells the story of how the priceless literary remains of this ancient city’s golden age were smuggled to safety after al-Qaida jihadis took over and imposed sharia law in April 2012. It reads like a sort of Schindler’s List for medieval African manuscripts and is an exemplary work of investigative journalism that is also a wonderfully colourful book of history and travel.

Martha Kearney

Home Fire; House of Names; Autumn

Why do some people become radicalised? It’s a question I’ve explored with experts on air, but perhaps fiction can provide greater insight. Kamila Shamsie’s powerful novel Home Fire (Bloomsbury Circus), inspired by Sophocles’s Antigone, did just that. Colm Tóibín also draws on Greek tragedy for his masterly House of Names (Viking). The escalation of violence and desire for revenge has deliberate echoes of the Irish Troubles. Autumn (Penguin) by Ali Smith, the story of an unlikely friendship, displays surreal imagination with her characteristic linguistic playfulness.

Ayobami Adebayo

What it Means When a Man Falls from the Sky; The Zoo; When I Hit You

I’d been anticipating Lesley Nneka Arimah’s debut since I read one of her stories years ago, and with its remarkable range and exquisite prose, What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky (Tinder Press) did not disappoint. In The Zoo (Faber), Christopher Wilson reimagines Stalin’s final days in power through the eyes of Yuri, a brain-damaged boy who becomes the dictator’s food taster. The result is a witty, tender, entertaining and sinister satire. Meena Kandasamy’s vivid, sharp and precise writing makes a triumph of When I Hit You: Or, a Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife (Atlantic), her searing and unflinching portrait of an abusive marriage.

David Kynaston

Joining the Dots; Our History of the 20th Century

Joining the Dots (HarperCollins) by the social historian Juliet Gardiner is such an accomplished and intensely evocative memoir that it will become in time an integral part of our understanding of postwar Britain. It is also, at a personal level, a journey of courage and determination. Travis Elborough’s resourceful, finely judged compilation, Our History of the 20th Century (Michael O’Mara Books), complements it well, drawing on an eclectic range of diaries and letters to open up the story of modern Britain.

Tom Holland

Viking Britain; Manhattan Beach; The Art of Failing

Fresh, vivid and impeccably researched, Thomas Williams’s Viking Britain (HarperCollins) was the most rip-roaring work of nonfiction I read this year. The novel I most enjoyed was Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach (Corsair), a historical thriller that was quite as visionary and stylish as one would expect from the author. The funniest book was Anthony McGowan’s The Art of Failing (Oneworld), which alternates self-mocking slapstick with flashes of weirdness reminiscent of Gogol.

Tahmima Anam

Home Fire

The standout book of the year for me is Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire (Bloomsbury Circus). It’s a modern retelling of Antigone set among a family divided by politics, love, and radicalism. In less than 300 pages, it managed to do all the things I want novels to do – tell me something about the world, give me a tiny glimpse into the otherness of others, and, most of all, give me that ache of longing as I turned the last page and realised I would never meet these characters again.

Rohan Silva

Fresh Complaint; A Place for All People

I adored Fresh Complaint (4th Estate), the new collection of short stories by Pulitzer prize-winning novelist Jeffrey Eugenides – it’s beautifully written and couldn’t be more topical, with tales of rape allegations on campus and transgender teens. Architect Richard Rogers’s memoir A Place for All People (Canongate) was my other favourite book of the year, showing how our cities could be fairer, greener and more beautiful.

Mariella Frostrup

American War; Little Fires Everywhere; Exit West

America’s tortured present lends unsettling believability to American War (Picador), the dystopian debut from journalist Omar El Akkad with its late 21st-century picture of a second civil war, fought over fossil fuel in a US devastated by environmental disaster. Brilliantly imagined, it’s both a timely tale and a salutary warning. Little Fires Everywhere (Little, Brown) is the second novel from Celeste Ng and manages to combine a thought-provoking story of race, belonging, motherhood and the cracked face of smug liberalism with the pace of a page-turner. Mohsin Hamid always makes you think and his Booker-nominated novel Exit West (Hamish Hamilton) is a beautiful, poignant story of love, longing and the agony of being uprooted and displaced among the migrating millions.

Linda Grant

Love & Fame; Reservoir 13; The Dark Flood Rises

Susie Boyt’s new novel Love & Fame (Virago) is characterised by the individuality of her voice. She writes sentences with the nuance of a playful Henry James, exploring grief with wit and wisdom. Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 (4th Estate), which was unlucky not to have been Booker-shortlisted, is a mesmerising account of landscape, daily life and, running through it, a deepening mystery about a missing girl. Breathtaking. Margaret Drabble’s The Dark Flood Rises (Canongate) is an absolute tour de force about old age and dying. Scandalous that it wasn’t a major prize-winner.

Frank Cottrell-Boyce

The Lost Words; Dethroning Mammon; Dislocating the Orient

As so often, the most beautiful and thought-provoking book I’ve read this year was a children’s picture book, The Lost Words (Hamish Hamilton), about the way words help us see more clearly, in which Robert Macfarlane’s charms are brought to life by Jackie Morris’s dazzling images. Justin Welby’s brisk, challenging Dethroning Mammon (Bloomsbury) was originally a Lent book but would work just as well for new year. We should probably read it as a nation because it would sort out our priorities. And then Daniel Foliard’s Dislocating the Orient: British Maps and the Making of the Middle East 1854-1921 (University of Chicago Press); I can’t understand why our kids are taught all about Vietnam but not this. We are all living with the fallout from the Sykes-Picot agreement.

Paul Murray

First Love; A State of Freedom; Lincoln in the Bardo

Gwendoline Riley’s First Love (Granta) tells the story of a young woman in an abusive relationship. It goes to some dark places, but Riley’s prose is so electric, so alive with humour and insight and passion, that by the end you will want to stand up and cheer. A State of Freedom (Chatto & Windus) by Neel Mukherjee also shows people living at their limit; it’s a brave and frequently devastating novel whose themes of displacement and dehumanisation are all too timely. I read it six months ago but the part about the bear still gives me the shivers. Lincoln in the Bardo (Bloomsbury) was every bit as wonderful as I expected from the great George Saunders.

Emma Healey

Little Labours; You Will Know Me

A friend gave me Little Labours (4th Estate) by Rivka Galchen after my daughter was born in June. It’s a funny, profound memoir that’s sort of about what it’s like to be a new mother, but is really about lots of other things including Japanese literature and the freedom to judge others. It’s also a very short book, written in brief, titled sections, and therefore ideal for sleep-deprived parents. I’m a huge fan of Megan Abbott and loved You Will Know Me (Picador) just as much as her previous explorations into the dark, disturbing, strangely heroic world of teenage girls. She’s the queen of the uncanny analogy (someone carves a ham, “pink as a newborn”) and knows just how to draw the reader into the characters’ dangerous, painful lives and how to make those lives mysterious. Her newest novel is intriguing and entertaining from the first page.

Helen Simpson

Go, Went, Gone; Midwinter Break; Conversations With Friends

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Go, Went, Gone (a title catchier in the original, Gehen, Ging, Gegangen) (Granta) is a deeply thoughtful and involving novel about migrancy now. Retired ex-GDR classics professor Richard, himself unhoused by war in infancy, befriends a group of African refugees in Berlin: grippingly interrogatory fiction. Bernard MacLaverty’s Midwinter Break (Jonathan Cape) shows a five-decade marriage unspooling over a long weekend in Amsterdam; 26-year-old Sally Rooney’s Conversations With Friends (Faber) is a latterday Bonjour Tristesse: brave and touching love stories, both of them.

Curtis Sittenfeld

The History of the Future; The Rules Do Not Apply

There are two 2017 books of nonfiction that have really stayed with me. The History of the Future (Coffee House Press) by Edward McPherson is a collection of impressively researched yet conversational essays about environmental degradation, place and time. The Rules Do Not Apply (Little, Brown) by Ariel Levy is simultaneously the personal story of a dramatic miscarriage, a frank, powerful look at shifting gender roles and how we make a life for ourselves, and an inside glimpse into Levy’s work as a journalist for the New Yorker.

Taiye Selasi

Things That Happened Before the Earthquake; Always Another Country; Freshwater

Chiara Barzini’s Things That Happened Before the Earthquake (Doubleday) strikes that rarest balance: a brilliant literary novel with all the effortless delights of a beach read. It’s a new-girl-in-town Bildungsroman that follows a precocious Italian teenager through 1990s Los Angeles. Sisonke Msimang’s Always Another Country (Jonathan Ball) is my favourite kind of memoir, so lyrical and dreamlike that it reads like a novel. It’s an artful meditation on exile and return, womanhood and motherhood unfolding against the backdrop of post-apartheid South African politics. Freshwater (Grove Atlantic) by Akwaeke Emezi is sheer perfection: sexy, sensual, spiritual, wise. One of the most dazzling debuts I’ve ever read. Ever since falling in love with Milan Kundera in secondary school, I’ve been obsessed with love triangles.

Katie Roiphe

Difficult Women; Transit; Forest Dark

The first book I loved this year was the NYRB reissue of David Plante’s Difficult Women, an incredible first-hand account of his encounters with three prickly and charismatic women: Jean Rhys, Germaine Greer and Sonia Orwell. Another book that stands out is Rachel Cusk’s Transit (Vintage), part of her masterful trilogy about a woman in a moment of radical transition (a genre I generally love, which also includes Nicole Krauss’s excellent Forest Dark (Bloomsbury).

Marina Warner

A Chill in the Air; The Golden Legend; Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms

Iris Origo’s A Chill in the Air: An Italian War Diary 1939-1940 (Pushkin Press) unfolds from week to week the horrible confusion, fear and misery as Mussolini shouted and swaggered; her clear-eyed account reads with truly alarming timeliness. Nadeem Aslam interweaves rich, poetic symbols with stark political realities in The Golden Legend (Faber) and manages to keep up hope in the strength of love and imagination. The art of the Brazilian-born Lygia Pape was a revelation to me: potent, playful and sometimes sublime works (Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms, ed. Iria Candela et al, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Joe Dunthorne

The Evenings; Conversations With Friends

I loved The Evenings (Pushkin Press) by Gerard Reve, surely the funniest novel ever written about boredom. It’s a classic of Dutch literature – first published in 1947 – but has only just found its way into English. The translation by Sam Garrett is perfect. I also adored Conversations With Friends (Faber) by Sally Rooney; a witty, nuanced and perfectly observed novel of modern love and friendship.

John Gray

Six Minutes in May; My House of Sky

Using new evidence with a novelist’s feeling for personality and atmosphere, Nicholas Shakespeare’s Six Minutes in May: How Churchill Unexpectedly Became Prime Minister (Harvill Secker) tells how a military disaster, parliamentary intrigues, a hidden love affair and a six-minute meeting enabled Winston Churchill to come to power. Reading this unputdownable story, I was reminded how the fate of the world can turn on the fall of a leaf. I’ve been engrossed by My House of Sky: the Life of JA Baker (Little Toller Books) by Hetty Saunders. This definitive biography of the author of The Peregrine, Baker’s lyrical account of his 10-year struggle to see the world through the eyes of the falcon, is a pioneering study of a solitary British visionary who recorded his attempt to break open the doors of perception in prose of astonishing power and originality.

Rupert Thomson

First Love; Madame Zero; Night Sky with Exit Wounds

Gwendoline Riley is a writer who cuts right to the heart of things, and her fifth novel, First Love (Granta), is predictably raw, fierce and true. If you like your fiction reassuring, look elsewhere. Sarah Hall is another voice I love. Her new book of short stories, Madame Zero (Faber), is a showcase for her clean, vivid style and her surreal, often feral imagination. Ocean Vuong’s collection of poems, Night Sky With Exit Wounds (Jonathan Cape), startled me with its urgency and its relevance. An eerily sure-footed debut.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett

Days Without End; Smile

Two brilliant Irish novels stood out, one lushly lyrical, one laconic, both so well written they make pain into literary delight. Days Without End (Faber), Sebastian Barry’s novel of war and defiant love, is as full of outrage and blood and grief as one of Kurosawa’s Shakespearean movies and it’s as gorgeously beautiful too. Roddy Doyle’s Smile (Jonathan Cape) is achingly sad and ruefully perceptive, exquisitely balancing anger with sympathy.

Kirsty Wark

Manhattan Beach; Days Without End; Appointment in Arezzo

One of the joys of my reading year was Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach (Little, Brown). She tells an intimate and unusual story set in Brooklyn in the second world war, centred around the flinty Anna Kerrigan who becomes the only woman training to be a diver in the Navy Yard, and whose difficult home life is drawn with great compassion. Egan captures marvellously the precarious heightened atmosphere of wartime New York. The savage beauty of Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End (Faber) is imprinted on my brain. The historical research in the story of Thomas McNulty, who left Ireland in the famine, is woven perfectly though this dark violent tale of Thomas and John Cole, lovers caught up in the Indian wars and the American civil war. Alan Taylor’s Appointment in Arezzo (Polygon), his account of his long friendship with Muriel Spark, about whom I am making a BBC documentary, is an insightful, fond and gossipy read, with a Sparkian title to boot.

Louise Doughty

Ghachar Ghochar; Stay With Me; I Am, I Am, I Am

There have been a lot of bells and whistles in fiction in 2017 and, while it’s been a stellar year for inventiveness, I’ve also enjoyed two novels that utilised the underrated power of a simple story, well told. Ghachar Ghochar (Faber) by Vivek Shanbhag, translated from the Kannada by Srinath Perur, is a seemingly straightforward tale of a Bangalore family who come into wealth. Its gently comic tone belies a stunning satire, the full power of which is only apparent as the horror of the ending becomes clear. The Women’s prize-shortlisted Stay With Me (Canongate) by Ayòbámi Adébáyò had me hooked from the start with its portrait of marital disharmony in 1980s Nigeria. But if you want evidence that life can be just as dramatic as fiction, you couldn’t wish for better than Maggie O’Farrell’s stunning memoir, I Am, I Am, I Am (Headline).

Sarah Winman

The Boy Behind the Curtain; Reservoir 13

Tim Winton is a favourite novelist of mine. Always has been. So to read The Boy Behind the Curtain (Picador), his collection of autobiographical stories and essays, was a total joy. Here are the influences that shaped Cloudstreet, Breath, The Riders, et al. In one essay, he writes about the gut-churning process and despair of fiction writing. I felt sick. Wonderful. I was handed Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 (4th Estate) and told: “See what you think.” What I think is that it’s remarkable. Lyrical, restrained and structurally brilliant. I’ve never read anything quite like it. The book

Julian Baggini

Be Like the Fox; The Infidel and the Professor; The Enigma of Reason

Erica Benner’s Be Like the Fox (Allen Lane) challenged us to rethink Machiavelli, while Dennis C Rasmussen’s The Infidel and the Professor (University Press Group) shone a deserved spotlight on David Hume and Adam Smith. But the standout book of the year was The Enigma of Reason (Allen Lane) by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. The idea that conscious, rational thought is largely window dressing has become the new common sense. Mercier and Sperber show that rationality is primarily social not solitary and has only been debunked because it has been misunderstood.

Sebastian Faulks

Enemies and Neighbours; The Novel of the Century

I am very much enjoying Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017 (Allen Lane) by Ian Black. I also raced through The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventure of Les Misérables (Particular Books) by David Bellos.

SJ Watson

The Fact of a Body; Tin Man

The Fact of a Body by Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich is an extraordinary book, weaving as it does the story of the author’s own childhood abuse at the hands of a grandfather into the (also true) story of a convicted child killer on death row in whose retrial she is involved. It’s a complex, difficult, essential read, as is Sarah Winman’s third novel, Tin Man, a beautiful book focusing on love, loss and sexual identity, which I can’t recommend highly enough.

Jenni Murray

Elmet; Be a Man

My favourite books of 2017 were, first, Elmet (JM Originals) by Fiona Mozley. It’s an amazingly brilliant debut novel which landed on the Booker shortlist and is a work of extraordinary Yorkshire grit. The landscape of my home county is evoked beautifully. The language is exquisite and the anger at the all-powerful wealthy landowner’s influence on the right to own one’s home leaps from the page. Second was Be a Man by Chris Hemmings (Biteback). A 30-year-old details the pressures of traditional masculinity on a growing boy, the lad phase and the maturing male’s need to comprehend and embrace the feminist project. Should be read by every parent, teacher, man and boy.

Chigozie Obioma

What Language Do I Dream In?; Lincold in the Bardo; Days Without End

I enjoyed What Language Do I Dream In? by Elena Lappin (Virago). She creates an acute sense of tension, and the way she loops explosive events in her life – discovering that her father was not, in fact, her father – into the philosophy around art and language is skilful and riveting. George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo (Bloomsbury) is one of the books where the jacket description gets it right: they use the word “kaleidoscopic” to describe this ingenious, polyphonic structure that is at once as entrancing as it is beautiful. In Days Without End (Faber), Sebastian Barry employed a rich, flourishing cascade of 19th-century vocabulary to create an atmospheric novel of friendship, war, immigration and the fragilities of the human life. It’s a powerful book.

Amma Asante

The Good Daugher; Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race

The Good Daughter by Karin Slaughter (HarperCollins) is genuinely disturbing and so skilfully crafted, you feel, taste and smell the world as you are sucked in by its unpredictable twists and turns. I found Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge (Bloomsbury) timely and resonant. The author’s passages on intersectionality are particularly poignant. It’s a powerful and important read, relevant and accessible whatever your race.

Damian Barr

Winter; As Kingfishers Catch Fire

Ali Smith’s Winter (Hamish Hamilton) is no cosy, comfort read. It’s a brisk frosty walk under skies that could open at any moment revealing anything but snow. I’ll be unpicking it for months. As Kingfishers Catch Fire (Little, Brown) is a memoir/gallimaufry of ornithological obsession by Alex Preston. He watches birds in the sky and on the page darting between myths, stories and memoir like a swift. The characterful illustrations by Neil Gower add a whole new dimension to this gorgeous book.

Frances Hardinge

Things a Bright Girl Can Do; We Come Apart; The Island at the End of Everything

Things a Bright Girl Can Do by Sally Nicholls (Andersen Press) follows three fallible yet formidable teenage girls caught up in the fight for women’s votes. We’re shown the intricacies of this turbulent period in a vivid, hard-hitting, funny and emotionally compelling way. We Come Apart, (Bloomsbury) co-written by Sarah Crossan and Brian Conaghan, recounts the romance of two maltreated teens through sparse, grittily powerful verse. Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s The Island at the End of Everything (Chicken House) is a beautiful, haunting tale of leprosy, lepidoptery and loyalty.

Geoff Dyer

The Unwomanly Face of War; The Sparsholt Affair

Nothing can quite prepare the reader for the shattering force of The Unwomanly Face of War (Penguin), Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history of Soviet women in the second world war. In the midst of such colossal suffering hundreds of little details stick in the mind, like the trail of blood left as a group of women march to – not from – the front because they are so poorly equipped, none have sanitary wear. I had the distinct sense, on finishing Alan Hollinghurst’s latest novel, that I might have read next year’s Booker-winner before this year’s had even been announced. The Sparsholt Affair (Picador) is a sweeping and intimate masterpiece, full of sensual pleasures and observational wisdom.

Paula Hawkins

Little Fires Everywhere; The Fact of a Body; Reservoir 13

Beginning with a house fire set by a teenager, the flames quickly spread across Celeste Ng’s suburban idyll in Little Fires Everywhere (Little, Brown), a sharp and nuanced tale of race and family in 1990s America. The Fact of a Body by Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich (Macmillan) is part memoir, part true crime, wholly brilliant. Bleak subject matter is expertly handled as Marzano-Lesnevich challenges us to see both perpetrators and victims from every possible angle. Perfectly paced and beautifully observed, Jon McGregor defies expectations in Reservoir 13 (4th Estate), his graceful and compelling portrait of a community coming to terms with tragedy.

Lucy Davies

Cove; The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter; The Sellout; A Life of My Own; Falling Awake; Syria: Recipes from Home

Books that have made my heart race, or swell, with their brilliance this year include Cynan Jones’s beautiful landscape writing of the spirit and the sea in Cove (Granta); the sublime craft and fearless ambition in Kia Corthron’s The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (Seven Stories); Paul Beatty’s blazing The Sellout (Oneworld); Claire Tomalin’s ambushingly poignant A Life of My Own (Viking); and Alice Oswald’s Falling Awake (Jonathan Cape) which I go back to and back to. I read a lot of cookbooks – a beautiful highlight was Syria: Recipes from Home by Itab Azzam and Dina Mousawi (Orion).

Lara Feigel

The Idiot; Conversations With Friends; All the Beloved Ghosts; Mrs Osmond

I’ve been particularly impressed by two conversational novels about intelligent, self-conscious young women: Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (Jonathan Cape) and Sally Rooney’s Conversations With Friends (Faber). Both created worlds and characters you live with and talk to and miss after finishing the book. I don’t usually read much short fiction but I loved Alison MacLeod’s All the Beloved Ghosts (Bloomsbury). MacLeod is dazzlingly good at evoking a whole life through a single snapshot and at bending and stretching her prose as she moves between an impressive range of narrative personae. More recently, I’ve just read John Banville’s Mrs Osmond (Viking), an astonishing act of literary ventriloquism that is so successful it felt like discovering a new Henry James novel.

Alex Preston

The Lost Words; The Sparsholt Affair; The Book of Dust volume One: La Belle Sauvage

Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris have made a thing of astonishing beauty in their The Lost Words (Hamish Hamilton). It’s a book to gift and to treasure – generous, luminous, profound. I was glad George Saunders won the Man Booker and for next year’s prize it’s hard to look beyond Alan Hollinghurst’s masterful The Sparsholt Affair (Picador), which I found thrillingly stylish and gripping. It’d be good to see Philip Pullman’s The Book of Dust, Volume One: La Belle Sauvage (Random House) on the list – a brilliant novel whether you’re nine or 90.

Katharine Norbury

La Belle Sauvage; The Bedlam Stacks; A New Map of Wonders

Philip Pullman’s The Book of Dust, Volume One: La Belle Sauvage (Random House) creaks with mystery and burns with passion and the thrill of what it is to be human. Natasha Pulley’s The Bedlam Stacks (Bloomsbury) is an immense treat for lovers of both historical fiction and the surreal. And Caspar Henderson has created A New Map of Wonders (Granta) that reveals the sublime from his garden shed and had me weeping with relief that wonder is so close at hand.

Chris Mullin

Life After Life; Called to Account

By far the best book I have read this year is Life After Life (Gill Books), the autobiography of Paddy Armstrong, one of four innocent people convicted of the Guildford and Woolwich pub bombings. Ghosted by Irish journalist Mary Elaine Tynan, a beautifully written account of extraordinary events. My other favourite is Called to Account (Little, Brown), by former chair of the public accounts committee, Margaret Hodge. A shocking exposé of corporate misbehaviour and government waste, it has not had the attention it deserves.

Sally Rooney

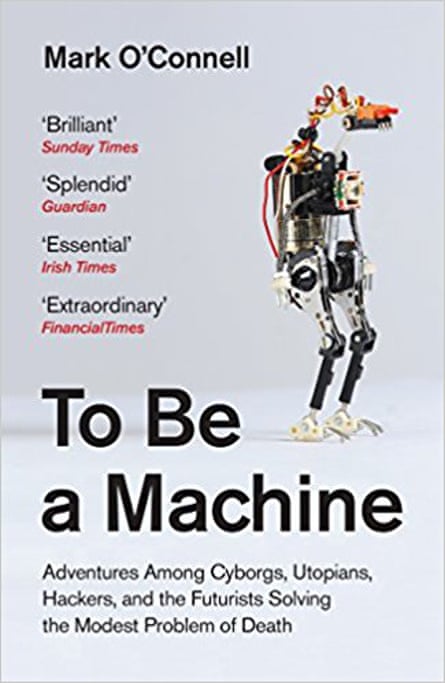

The Idiot; To Be a Machine; The Ambassadors

This year I read and loved Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (Jonathan Cape) – which apart from its intellectual heft is page-for-page one of the funniest novels I’ve ever read. In nonfiction, this was the year of Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine (Granta), a profoundly unsettling and brilliant account of technology and human life. Though it wasn’t published in 2017 (more like 1903), Henry James’s lively novel The Ambassadors (available from Arcturus) was one of my favourite literary discoveries this year.