In April 2012, the jihadist army of the Saharan branch of al-Qaida drove a fleet of their armoured pick-up trucks into the centre of the ancient caravan town of Timbuktu in northern Mali. As black flags were hoisted atop the minarets, and as trapped and terrified government conscripts scrambled out of their uniforms, the jihadists began imposing their own puritanical interpretation of sharia law. Music was forbidden, modest clothing was forced on the women, stoning was imposed as a punishment for adultery and a war declared on “unIslamic superstition”.

This began with an attack on Timbuktu’s most revered djinn. Al-Farouk was said to manifest himself as “a ghostly figure … dressed all in white, with a length of cotton bound around his face in the Tuareg style and riding a white horse”. As Charlie English explains in The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu, the djinn was a guardian, looked on locally as “a talismanic symbol of the city who for centuries had protected it from malicious spirits”, with a “monument on a traffic island in the Place de l’Indépendence”. But for the Salafists of the AQIM – al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb – he was merely a false idol, and soon after their arrival in Timbuktu, one of the jihadists climbed on to the monument and decapitated the statue of the horseman.

The many mausoleums of the city’s saints were the next target: by June, the jihadists had embarked on a full-scale assault on the ancient tombs scattered around Timbuktu. They lectured the townspeople on the evils of their cult of protector-saints, then began to smash the intricate carvings with pickaxes and metal crowbars.

The realisation that Timbuktu’s fragile heritage was in danger set off alarm bells across the world. The city was once one of Africa’s most revered centres of learning and the arts. From the 13th century onwards, but particularly during the great days of the Songhai empire, which reached its peak during the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu became the West African equivalent of Oxbridge or the Ivy League, pullulating with scholars busy copying out old Arabic manuscripts and composing new works of theology, history and science.

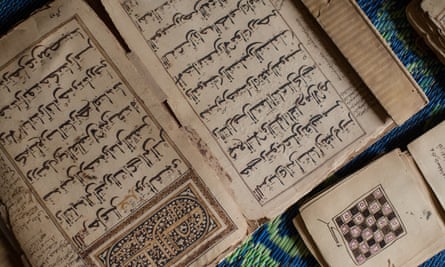

In 2012 the literary remains of this golden age still lay stacked in libraries around the city. Only in recent decades had scholars come to appreciate the extraordinary intellectual wealth that lay hidden in private homes in this now remote but once cosmopolitan centre of learning. Searches had recently revealed the city to be groaning with medieval manuscripts “so numerous”, English writes, “that no one really knows quite how many there are, though they are reckoned [to be] in the tens or even hundreds of thousands”.

For African historians, the realisation during the late 1990s of the full scale of Timbuktu’s intellectual heritage was the equivalent of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls for scholars of Judaism in the 1950s. When the African American academic Henry Louis Gates Jr visited Timbuktu in 1997 he actually burst into tears at the discovery of the extraordinary literary riches. He had always taught his Harvard students that “there was no written history in Africa, that it was all oral. Now that he had seen these manuscripts, everything had changed.”

Yet with the coming of al-Qaida, there was now a widespread fear that this huge treasure trove, the study of which had only just begun, could go the way of the Baghdad, Kabul or Palmyra museums, or the Bamiyan Buddhas. Before long, efforts began to smuggle the most important of the manuscripts out of Timbuktu and to somehow get them to safety in Bamako, the capital of Mali. The story of how this was done forms the narrative backbone of The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu, which consequently reads like a sort of Schindler’s list for medieval African manuscripts, “a modern day folk tale that proved irresistible, with such resonant, universal themes of good versus evil, books versus guns, fanatics versus moderates”.

English first came across the story when he was head of international news at this paper, but he had been fascinated by Timbuktu since he first visited it in his late teens. Realising the potential of the story he had to tell, he went to Mali to meet the people involved and to record their tale. What he discovered was rather different and more morally complex than initial reports had indicated. He also begun to construct a more complicated framework for his book.

Fascinated by the history of the town and the attempts by 18th and 19th-century western explorers to reach what they imagined to be an African Eldorado, glinting with gilded domes and a place that could make their fortunes and immortalise their names, he decided to interweave the story of the al-Qaida occupation, and the efforts to save the city’s literary heritage, with accounts of early attempts to reach and understand Timbuktu, and the role that dreams, imagination and myth-making all played in the process.

Bruce Chatwin once observed that there are actually two Timbuktus: one the real place – “a tired caravan town where the Niger bends into the Sahara” – and another “altogether more fabulous, a legendary city in a never-never land, the Timbuktu of the mind”. This mythical Timbuktu was certainly partly the creation of western orientalists, but as English astutely notes, it was a myth that Malians also subscribed to and helped create. After all, the ancient histories of Timbuktu themselves painted a picture of “a virtuous, pure, undefiled and proud city, blessed with divine favour” that “had no parallel in the land of the blacks”. As English persists in his investigations he realises that his own story of the manuscript smugglers had also undergone a process of mythologisation at the hands of his informants.

There is no doubt that al-Qaida did represent a threat to the Timbuktu libraries, and indeed around 4,200 manuscripts were burned by the jihadists as they were leaving town – just as Isis last month destroyed the great mosque of Mosul during its retreat. Equally, there is no doubt that the librarians went to heroic lengths to protect the treasures under their guardianship, burying some and smuggling out others. But as his research progressed, he became increasingly suspicious that the scale of the rescue operation had been exaggerated by the heroes of his tale, as they began to understand the extent of the willingness of western donors to wire vast quantities of money to Mali in order to get the precious manuscripts out to safety.

One librarian claimed to have organised a small army of smugglers lining the route to Bamako, who carried hundreds of thousands of manuscripts out on convoys of lorries and later, as the French Foreign Legion moved north to take on al-Qaida, in fleets of small river boats down the Niger, braving pirates, ambushes, corrupt government troops and trigger-happy French helicopter patrols. Of these stories English grew to be profoundly sceptical. He acknowledges that some manuscripts were indeed saved in actions that “undoubtedly took chutzpah and courage, from the directors of the libraries as well as more junior colleagues, who braved the jihadiststs’ sharia punishments”. But “from these fundamentals, the operation was spun into something larger and more dangerous than it really was”. The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu is an exemplary piece of investigative journalism that is also a wonderfully colourful book of history and travel. Above all, it is a work of intellectual honesty that represents narrative non-fiction at its most satisfying and engaging.

William Dalrymple and Anita Anand’s Koh-i-Noor: A History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond is published by Bloomsbury.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion