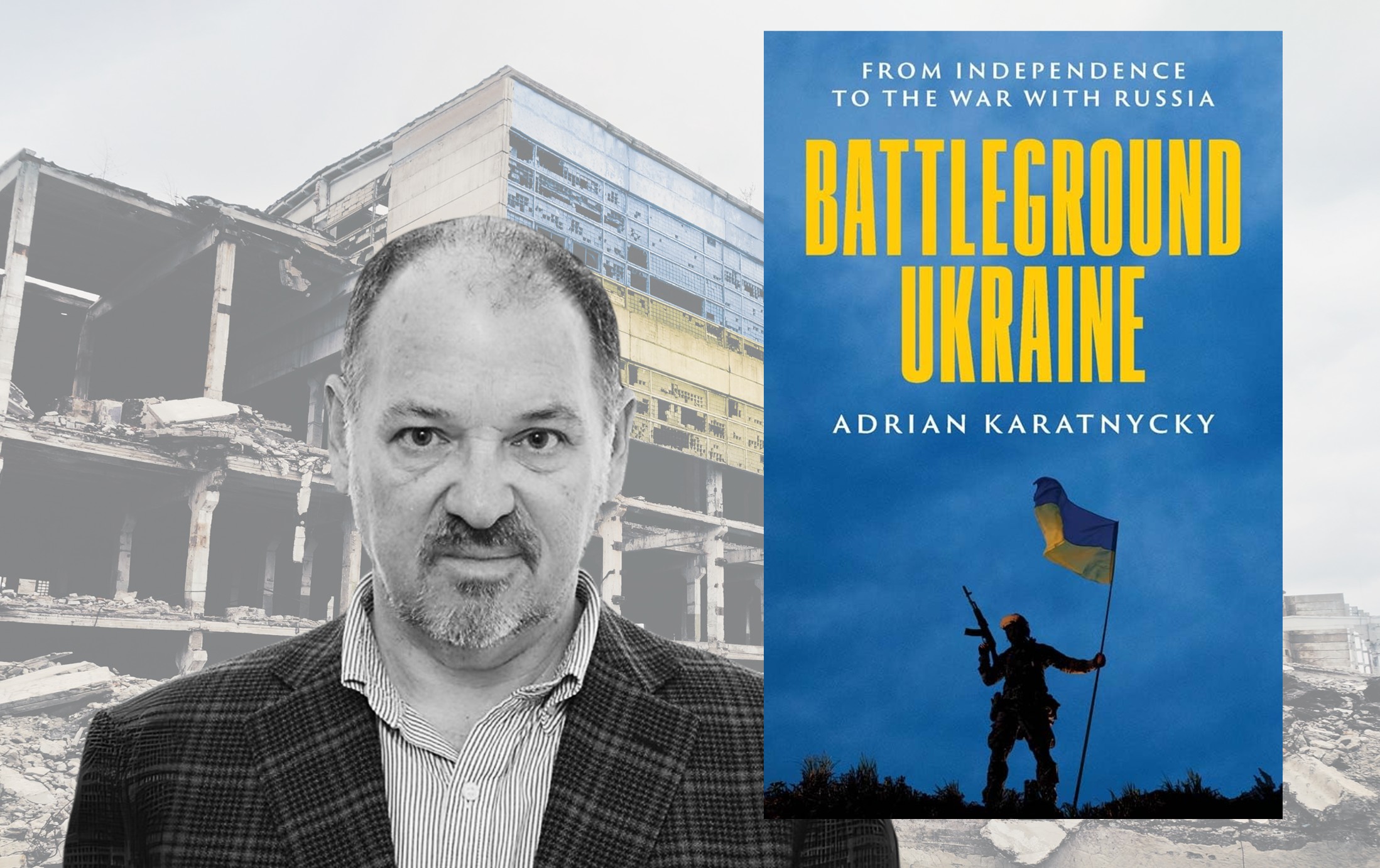

Adrian Karatnycky and "Battleground Ukraine: From Independence to the War with Russia"

For over three decades, Adrian Karatnycky has been one of the leading analysts of Ukraine in the United States. He has consulted civil society and politicians and written extensively about the country for various newspapers and publications, including Foreign Policy, The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Affairs, The Atlantic, and National Review.

His latest book, Battleground Ukraine: From Independence to the War with Russia, published in 2024, has been praised for exploring the history of the modern Ukrainian state through the tenures of its six democratically elected presidents, who have led the country since it declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Through eyewitness accounts and interactions with key Ukrainian politicians over nearly thirty-five years, Karatnycky provides a framework for understanding Ukrainian politics, society, culture, and relations with Russia. This is especially critical as Ukraine defends its very existence against Russia, which illegally annexed Crimea in 2014, subsequently establishing puppet regimes in the country's Donbas region in the east and ultimately invading the nation on 24 February 2022.

Karatnycky recently spoke with Natalia A. Feduschak, Director of Communications for the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, about the current efforts by the new administration in the United States to end the Russo-Ukrainian war, how Ukraine's presidents impacted Ukrainian society, and how the nation has evolved over the last thirty-three years.

With a new administration in Washington, discussions about conducting presidential elections in Ukraine have intensified. This would contradict the country's constitution, which prohibits elections during martial law, a state that has been in effect in Ukraine since Russia's illegal invasion in 2022. Should Ukraine proceed with elections?

There should be no election. Ukrainians think political contestation is disruptive at a time of war. They want people who are overseas to come back home. All this talk within the Trump Administration about wanting someone else at the top only solidifies the Ukrainians' belief that you can only have one leader at a time during a time of war and has led to increased backing for Volodymyr Zelensky. Ukrainians believe they can put off to the future that decision and don't want to make such a decision in the middle of a war. They also don't want to make such a decision in the middle of something tentative, like a partial ceasefire. Because maximum participation of people, including those who left the country, is essential. And that's about seven million people living outside of Ukraine, by most estimates. You must figure out how these people can participate in that process. It would be very hard to do given the limited diplomatic presence and the capacity of embassies and consulates to handle those elections. Some people like Senator Lindsey Graham have argued that. But they, just like President Trump, think: 'We need someone new to talk with. We need to rejigger it.' What they don't understand is whoever is going to be in office will be making decisions within the context of it being acceptable to the Ukrainian people.

The good news is that Ukrainians are now more willing to settle at the current division of territories, not accept them as permanent nor to recognize their illegal annexation by Russia, but to say, "We're not going to fight beyond this point. We will work by other means to restore Ukraine to at least its 2014 or 2022 borders. We will have the aspiration that we want to see the entire configuration of Ukraine eventually rejoined into the fold in the way that the Baltic states, the West, and the United States thought about the Baltic states; they didn't recognize their incorporation into the Soviet Union." But again, I think that the problem is that there is a leadership in the United States at the very top that has very little knowledge of Ukraine, that developed its knowledge of Ukraine primarily from interaction with those who left the Soviet Union and were in the New York real estate business or were Russian-born or Ukrainian-born billionaires who have done business with Trump's entourage and some of the people that he's designated as his negotiators.

There's a lack of awareness in this cohort about what has happened in the last 35 years to the consolidation of the Ukrainian people, what they believe, what their red lines are, and not just what Zelensky is willing to give up or not give up. He is operating because Ukraine is a democracy, and Ukraine is a society that mobilizes peacefully when its government is not representing the public will. That is something that has to be taken into account. That is something, in a sense, what the book is about. It's about the genesis of the Ukraine we have today, the fighting Ukraine, the unified Ukraine. How did we get here, and how did Ukraine manage to preserve its democratic characteristics of fairly substantial pluralism, even at a time of war?

What would be the consequences globally of Ukraine not winning this war or losing a part of its territory? What would be the consequences of Ukraine falling?

Well, these are different things. The consequences of Ukraine losing its territory go well beyond what it means for Ukrainians. This is the first instance since the reconfiguration of the globe and since the creation of the United Nations where another state has, through invasion, annexed and occupied — and not just waged war — but annexed and occupied the territory of another sovereign state and incorporated it into its own. That was tried by Iraq with Kuwait, but that annexation was reversed. The only other instance of something like that happening was in Tibet. But Tibet had only one or two countries that recognized it as a state. It operated de facto independently of China. When China moved in with its questionable historical claims, nevertheless, it was not moving against a state that had diplomatic relations that were recognized as a subject of international law.

So, this would be the only instance of another country successfully annexing territory in eight decades. There have been some territorial disputes, but there was no territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia that had been settled diplomatically. The Falklands War may have been an attempt to grab land. But again, Argentina always disputed that territory. Russia formally accepted Crimea's incorporation into Ukraine, and certainly the Donbas, and certainly Mykolaiv and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. That is a dangerous precedent.

If it does not have serious consequences, it opens a Pandora's box for a potentially destabilizing precedent internationally.

But as to "What is victory?" Holding off Russia and maintaining 80% of the country, if not more, and maybe being able to exchange a piece of Russian territory for currently occupied Ukrainian land. These are incredible accomplishments of the Ukrainian people and the Ukrainian armed forces. And given what the prognosis was — that the country falling in three days — is itself a victory. It's a victory that has come at a great cost, but it shows the resilience of the Ukrainian people. It also shows a high degree of national unity. One of the things I talk about in the book is the role of civil society, pluralism, and the fact that many people have a voice inside society. The oligarchs don't have any voice. The state has a voice, but it is not all-powerful. Civil society and new business, the new elites that created a lot of stakeholders, gave people a sense of participation in society. The important thing that I didn't quite credit in the book but needs to be understood is that this social energy that was on the Maidan, the social energy that came out of the Orange Revolution, created a burgeoning civil society and a lot of social activism and cultural activism. All those things remind me of the power of social mobilization and how it can be converted into both patriotism and the energy to wage and fight a war because you're a stakeholder in that society in some sense. The French Revolution — and I'm not comparing Ukraine to the French Revolution — showed that the public energy generated by the revolution allowed the French to raise an army during the French Revolution of a million people because there was this huge social energy and social mobilization.

Ukraine's mobilization luckily occurred with the Maidan and generated the energy that allowed the country to defend itself in 2014. We should remember that Russia waged an all-out war in 2014 called the "Russian Spring." It was a hybrid war but was nevertheless an attempt to carve out maybe half of Ukrainian territory or more. That was the ambition of the Kremlin and the plan that Putin launched even two days before [former President Viktor] Yanukovych fled the country. Something I write about in my book is that on 20 February [2014], two days before Yanukovych fled Kyiv, Putin had already decided, 'Let's get as much as we can. Let's try to grab what we can.'

It's equally important to understand the precedent of this for international law. Moreover, it's important to understand the dynamics of what this is. It was a social victory for Ukraine and consolidated the people. And yes, the hardships of war, all the pain, the suffering of many people, their sacrifices, and what many people have given up. Nevertheless, I think Ukrainian solidarity is still pretty strong and I also would say that despite the radicalization that occurs in wartime, Ukrainian pragmatism is strong. So, all these factors today define victory as the preservation of sovereignty and the coherence of the state, while maintaining the lion's share of Ukrainian territory. That itself is a major victory.

If Ukraine doesn't have American support, is there enough ingenuity for Ukraine to militarily defend the territory it holds?

The short answer is there are alternatives. The main alternative is Europe, which has a GDP that, with the UK, is roughly ten times Russia's. This economic power should be able to sustain its own defense and contribute heavily to Ukraine's security. The fact that the European Union is talking about new $850 billion USD commitments to rebuilding their military capabilities and support for Ukraine is encouraging. And more importantly, for the next few years, if Europe has the will — and there's increasing discussion about it — there is the $300 billion USD of Russian hard currency reserves, most of which are in Europe.

Canada is the only country that has pledged that money to the aid Ukraine will receive from the Russian hard currency reserves they hold. But there's $300 billion USD right now. They're just using the interest. If you think about that $300 billion USD, the United States was giving $35 billion USD a year in military and economic aid to Ukraine over the first three years. That's what reached the Ukrainian people. There are additional costs for preparing the equipment, shipping the equipment and so on. The Ukrainians offered to absorb some of those costs, for example to fly things into Poland on Ukrainian transport planes with Ukrainian equipment and with Ukrainian workers. They were refused. Huge billions of dollars were spent on American contractors to do this, which could have been done much more cheaply.

The United States taxpayer has given $35-40 billion USD a year to support Ukraine over the last three years. This means the $300 billion USD in Russian hard currency reserves can replace an end to U.S. support and last another six or seven years. That's a very long time to preserve at least this level of support. Of course, that would require the United States to be willing to allow Ukraine and Europe to buy U.S. And it would require Europe also to scale up its support.

So, it is possible for Ukraine to defend itself without any U.S. support. It would be harder without U.S. intelligence cooperation and if the U.S. were to create a closer bond with Russia. But in the absence of peace, it will be very hard domestically, even for Donald Trump, to force a warming of relations with Russia while Russia is still engaged in aggression in Ukraine.

How has Ukrainian society changed since the country declared independence in 1991?

My book and other books describe where Ukraine is, where the people are, and what has happened to the Ukrainian nation over the more than three decades of independence. And it's really important for people in the West to understand that this moment represents the highest point of Ukrainian cultural, state, and military development in history dating from Kyivan-Rus.

Never has there been such a mobilized and unified Ukrainian society. The state has various means of mass communication and new technologies, such as the Internet, video, and decentralized information sharing. Never has so much information been shared in Ukrainian and in the interests of Ukrainian patriotism. Never has there been this much cultural ferment in Ukraine with Ukrainian content in Ukraine's history.

Yes, in the past there was folk culture. But people were living in villages and farmlands. When they moved into the cities, they were either in Polish- or Russian-majority environments. Ukrainians never before had such a fully developed modern civilization. Indeed, Ukraine has reached the highest pinnacle of Ukrainianness it has ever had. And this is the exact moment in which Putin decides to undo all that.

So my book is about everything that has happened in this sphere. It explains how this society gained energy and found itself and became more and more unified; how it fought off the challenge, first of economic instability and hyperinflation, then the challenge of oligarchs and the challenge of the old communist elite, and negotiated its way, often through civic ferment, in the right direction toward pluralism and democracy.

That process has been so important. It's why we have this resilient and unified country, which has in its head the same red lines when it comes to defense of its sovereignty and its territory. This is a pragmatic, common-sense approach.

Several excellent books have appeared in recent years that together explain where Ukraine is on this important trajectory. They help explain why it would be very hard to root out these ideas. It would require a sort of re-Stalinization of all of Ukraine, which we already see in the Russian-occupied territories.

Apart from the flow of millions of people who would leave the country because they can't live under Russian-style dictatorship, not to speak of the dominance of Russian culture and suppression of Ukrainian culture, what it would take to uproot the dominant ideas in Ukrainian society to implement what Putin cynically calls de-Nazification but is really the Ukrainianization of Ukraine, would be an impossible task without mass repression. It would require a massive gulag on a Stalin scale and Stalin-sized re-education campaigns, physical intimidation, torture, etc. All of which we've seen on a smaller scale in the newly occupied territories as Russia was attempting to frighten the population and suppress the Ukrainianness inside the areas it occupied.

How did Ukrainian society influence the country's presidents?

The first thing I want to say is none of the presidents, except possibly Victor Yushchenko [Ukraine's third president — Ed.], had on their agenda the systematic nurturing of Ukrainian culture and the deepening of Ukrainian identity. That was even the case with Petro Poroshenko [Ukraine's fifth president — Ed.] and certainly the early years of Volodymyr Zelensky. All of that came from society. Leonid Kravchuk [Ukraine's first president — Ed.], had a little feel for Western Ukrainian nationalism and national sentiment, and he was influenced to an extent by the cultural intelligentsia — but he was, in essence, a recovering Communist apparatchik — the Ukrainian cultural intelligentsia and the scale of Ukrainian mobilization in the early stages. They feared society because they saw the large demonstrations: They saw the Revolution on Granite, they saw the human chain [Chain of Unity — Ed.], worker ferment, and so on. So that has always been a dynamic that has always moved these leaders. Sovereignty and taking over the state meant that each of these leaders faced a challenge. That's why I call it a battleground. Battleground Ukraine is not just the current battleground. It's the battleground between Russia and imperial interests and the move towards sovereignty and Ukrainian identity. It's the battleground between civil society and the new businesses that are emerging. Entrepreneurial businesses on the one hand, and a kind of corrupt state and oligarchic elite on the other. And in between this, the pressure of the West, the lure of the West. Western economic and financial support. That is the playground, or the battleground, in which the Ukrainian identity takes shape.

All of Ukraine's presidents were and are influenced by society. They are influenced by the democratic process. They are influenced by the street. That creates constraints on what they do. If you think about Kravchuk, Kravchuk comes from the Communist elite. He comes from the establishment. He maintains a portion of that elite and merges it with a combination of the new civic activism, political prisoners, the former Communists, the Ukrainianized cultural elite. It creates a diverse mix. The next president, Leonid Kuchma, has a new force to deal with in the rising oligarchy, and he and the former red directors face this powerful new force of people who are sometimes using corrupt ways to take control of resources, power, and economic assets. Kuchma tries to adjudicate this. I think he shows some strength in dealing with it. He is also conditioned by the fact that he feels Russian pressure and quickly learns that you have to be on your guard because Russia is out there, creating trouble from the very beginning. Even if it's not then the official state policy of Russia, there is a deep Russian interest by many in the Russian elite to create trouble in Crimea — to build bases of relationships with pro-Russian elements inside the Donbas. That starts from the very early years of the Russian state. So, each of these presidents is dealing with this stuff.

How did Victor Yushchenko, Ukraine's third president, influence Ukraine? And what about Viktor Yanukovych, who proceeded him?

Victor Yushchenko was a prime minister. He was also head of the central bank. He was part of that establishment. But he is soon "mugged by reality". He's attacked because he's not a reliable enough partner for Kuchma. He's also viewed with suspicion because of his Ukrainian patriotism. He's the first president who tried to use some of the state's resources to elevate Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian history, all the stuff on ceremonial things, the rebuilding of the Cossack historical background, the lionization of past Ukrainian fighters for independence, Holodomor memorialization. He wore his patriotism on his sleeve like most Western leaders who have a patriotic voice. Most Ukrainian leaders before Yushchenko didn't speak about Ukrainianness and the state with that same kind of soulfulness and deep belief. And that's one of his strengths and one of his lasting contributions. Yushchenko begins to push the country towards Europe, towards a European identity. That's a pivot, creating a lot of public investment in Europe. Ukrainians see how Poland is doing, how the Czechs are doing, how all the neighboring states are doing and growing. It becomes a very attractive, aspirational aim.

Then, we go back to Yanukovych and another detour toward the past. Yanukovych wants to revert to playing off every political party, to maneuver between East and West, all of this to maximize his ability to enrich himself, to enrich his family, and his inner circle. His avarice leads to trouble and he becomes much too dependent on the Russians, especially when the country's hard currency reserves drop. He brings in a strong pro-Russian lobby, which is balanced to some extent by people who either want a two-vector policy or even a Europeanization policy. We must remember that Petro Poroshenko [Ukraine's fifth president — Ed.], was part of that government. But I think Yanukovych, in some sense, his approach is that he doesn't want to be a lackey of Putin's. That's his only redeeming characteristic. He wants to be the top dog. He has a lot of the characteristics of Donald Trump: "I'm the boss. I make all the decisions. Everybody falls into line." This kind of top-down thing. But despite such ambitions, he never succeeds in creating a very structured dictatorship. He never succeeds in taming the oligarchs. They're very unhappy with him. They try to undermine him in 2012 during parliamentary elections. He tries to get a parliamentary majority and fails even to get an absolute majority for the ruling party.

That's done partly by oligarchs who are worried that he's going to take too much power. He never fully consolidates an authoritarian state. It's unclear exactly how all the killings on the Maidan went; is this a Russian operation? I tend to believe, and I have argued in more detail elsewhere, that there was a coup in the collapse of Yanukovych, but that it was orchestrated to an extent by the Russian withdrawal of support for him within his inner circle. And when the Russians withdrew because the Russians wanted to take Crimea, take as much of Ukraine as they possibly could, they no longer backed him. That was the reason he fled the country. The security forces were not backing him. The power structures were infiltrated and run by Russians. There was also a heavy KGB leadership and FSB leadership presence inside Kyiv on the days of the Maidan.

And Putin, I think, was unhappy that Yanukovych hadn't just crushed the Maidan entirely. Putin saw that the Parliament had voted in the dictatorial laws, but the dictatorial laws didn't come with a complete crushing of the Maidan. I think Putin, for this reason, loses interest in Yanukovych and withdraws his support. That, as well as the public ferment, is what forced him from office.

What about Petro Poroshenko, the country's fifth president?

We have an interesting transition by a person who's also been a part of this establishment. Poroshenko was with Yushchenko. Poroshenko was with Yanukovych to a degree. He served in his government and was part of the establishment that had run Ukraine throughout. He was a technocrat, a businessman, a billionaire oligarch, or whatever. So, he was part of that system. And it was very interesting that when he was elected president, three months after the Maidan, in his inaugural speech, one word was missing. He never utters the word "Maidan." He never refers to it; he wants to move on. He wants to establish his legitimacy purely based on the election. And I think, in some sense, he alienates some of that base. Because he has this war going on, he is very careful in how he balances and deals with the other powerbrokers, the other oligarchs. He fights a few skirmishes with a few of them but never tries to take them on and so makes marginal progress. Some progress, but not as much as I think the West had hoped. But at that point, he's dealing with a hybrid war, where in the first year over 10,000 people die on both sides. This is a major, major conflagration.

He's very careful. He's careful to the point that he even holds back on some of the, I would say, demands for greater Ukrainianization, including the fact that he was reluctant to pass the Ukrainian language preference laws. Not things banning Russian but giving Ukrainian a more privileged position and some state encouragement and subsidies. It was Narodniy Front and [Arseniy] Yatsenyuk's group that was pushing that idea, along with the people from the Maidan. In the end, he went with it. But he was afraid it might alienate people in the east — there is this hybrid war, and we may get more people opposing us, etcetera.

He was a very cautious person who, at some points, showed great courage, like when he was with Yushchenko. That was when he was risking hundreds of millions of dollars. He was with the Maidan when he was risking his billions. So, there's a lot to say for him. Nevertheless, I think he was a person who was fairly cautious until the tail end when the campaign came. And then he ran against a person trying to overcome, who thought the effort to inject Ukrainianness into the debate was harmful.

That person was Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine's current president.

I think Zelensky didn't have a feel for nationalism or the force of patriotism growing inside society. He was also not sympathetic to or connected to the Maidan, except rhetorically in being opposed to the old establishment and the corruption in the society he saw. He had no deep links to civic activists and most people who joined his political movement. They came more from the business or technocratic sectors. They didn't come from the Maidan or the conscious Ukrainian forces. One of the embarrassing things I write about is when he goes to the Arsenal book fair, and he's asked, "What books did you purchase?" His response shows he knows nothing about what's going on in the huge ferment of Ukrainian culture. He answers weakly: "I bought a volume of Kobzar." This really means "I don't know anything about Ukrainian literature. The only thing I could think of, the only thing that spoke to me was something that is already embedded in every Ukrainian's identity and consciousness." He also gave a terrible New Year's speech about how differences don't matter, whether you warm to the Soviet past, whether you honor the Red Army, whether you honor the UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army — Ed.], whether you speak the Ukrainian language, who cares? We're just building a society. We just want to live better.

Only later, with the war, did he get this deeper awareness and understand the force of patriotism. He became a very patriotic, much more nationally conscious person, partly because Zelensky's great power is that he can feel where the public is. He can embody their will in a very clear-cut way. Was he a very successful president in peacetime? No. I think he was in trouble going into the second year. The war resuscitated his political fortunes and made him the unifying force — a figure around which Ukrainians rallied. His courage and his tough guy attitude were not just a stance. He really is a tough cookie, and he is a courageous guy. He figured out how to speak on behalf of the public, to the world, and also to embody the will of the nation. Which in my view, comes from his theatrical actor's ability, comedian's ability, to feel the audience and to play to the audience and to embody the audience's interests and desires and to express them.

This raises the question, 'What now?' We don't know when and how the war will end.

We're at the apex of Ukrainianness. We're also at a time where irrespective of how the peace negotiations go, even if Europe has substantial resources to help Ukraine, an ongoing war for a very long time will be terribly debilitating for society. But it's also debilitating for Russia. Many people believe the Russian economy is falling further and further behind. It's facing some severe difficulties, but the main difficulty is that it is not part of the AI revolution. It lost many of its young men who have left, especially those in the high-tech sector, programmers, and developers. All these guys left the country and are working, whether it's in Dubai or Thailand or Serbia or other outposts. They've fled to avoid potential conscription. All this creativity has been drained out of Russia. The Russian elite, including the security services, know that will have national security consequences if Russia falls further behind. This is probably why they're trying to see what they can get away with in Donald Trump: Whether they can get a lot of what they want vis-a-vis Ukraine but also open the door to an economic relationship to repeat the path the U.S. offered China. The U.S. created a rival and a threat by investing and buying into this idea that economic cooperation with a dictatorship is the path to good relations. But what it does is it just empowers a dictator who eventually becomes a bigger threat.

Russia wants to remain a big power. It sees long-term isolation from Europe and long-term isolation from half the world's economies as harmful to its interests and, therefore, potentially may not be willing to keep this going that long. This is why, if Europe stays with Ukraine, if the United States stays with Ukraine, even if there isn't a peace settlement, Russia will eventually come to terms and try to settle things.

As for the future of combat, General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, who is one of the heroes of the book, has referred to the idea of reducing the human footprint in combat and using technologies. With the rise of AI, robotics, Ukraine's innovations in drone warfare, more sophisticated missile warfare, and AI-driven self-operating attack vehicles, all these things offer compensation for Russia's numerical and resource advantages. If Ukraine maintains its unity, if Europe maintains its unity and ensures that the United States is not in a position to force Ukraine into de facto surrendering its sovereignty, the future is working on behalf of Ukraine. And one way or another, a quicker rather than a later settlement of the war. This is why I end my book on a fairly optimistic note because Ukraine has unified itself. Its chances of survival and maintaining its sovereignty, which is the real victory, are very high.

Even if that victory excludes returning to its 1991 borders?

The battle is not over territory. It's about the territory inside your mind. And how much is taken up by the colonial mind versus the free sovereign European, Ukrainian mind.

I think that the model for Ukraine is — even if they concede they won't recover this territory — they should only be conceding they will not use military means as part of the peace process. They will continue to fight diplomatically and insist that this is an integral part of the state. And they will hope that — as the Balts eventually found their freedom and were able to rejoin the community of nations — some of these territories, if not all of these territories, will be able to be returned by some other means at some other point in time. It took fifty years for the Baltic states to reenter Europe, but the U.S. never recognized their incorporation into the Soviet sphere. Ukrainians should be fighting for the fact that no peace settlement must ever recognize these territories as Russian. Certainly, no economic cooperation with Russia in the future should include those illegally confiscated areas.

Although all of Ukraine has been affected by the war, much of the fighting has taken place in Ukraine's east; the south has been attacked repeatedly. The region has historically been Russian-speaking and inhabited by the type of people Vladimir Putin says he wants to "protect" in Ukraine. And yet, this is where he has unleashed his greatest fury. How can this be explained?

There are several factors here. Number one, for these people to have developed a new sense of identity, they had to have something to turn towards. What they turned towards was, in a sense, the values that you yourself witnessed at the first congresses and conclaves of Rukh. It was an open, democratically oriented, culturally Ukrainian vision of the country where every ethnicity was welcome to join in that grand bargain. Support for human rights, support for democracy, support for a European Ukrainian identity, and acceptance and participation in the Ukrainian culture and language. That bargain is now the basis of what we would call the political nation that has come into being. A lot of people think that it was just the war that turned that part of Ukraine towards this civic nationalism.

But the other thing was, first, that for twenty-five years, there were values — you had a flag, you had athletes running under that flag. You had ceremonies, you learned Ukrainian history. Your children went to schools and were taught a narrative about Ukraine's identity. And so, no matter how you voted, that was still a part of your belief system in some ways, maybe sometimes in contrast with your ill-shaped identity.

But I think the problem was that the people who were kind of Russophone never wanted to be a part of Russia; they wanted to be different. They wanted to be culturally Russian. They had more of a Soviet orientation or a regional orientation. But the people who wanted to be a part of Russia were not that numerous in their self-definition. The other factor was that it was the land grab that occurred without the will of the people. Because we know that only a few thousand people took part in agitations in the Donbas and the criminals that came in and so on. People who saw this didn't like it. You saw the people from the east, by a margin of three- or four-to-one migrated towards Ukraine and not into Russia when they had the chance in 2022. The other factor was they didn't like the annexation of Crimea. It was regarded by Russian-speaking Ukrainians as an unjust and unfair thing. All of these things contributed.

They could only have allowed themselves to consolidate around a Ukrainian agenda and a Ukrainian identity because there was something open, something democratic, and something welcoming. With some conditions or standards that, yes, you can privately speak Russian, but this is a nation-state built for the Ukrainian people of all ethnic groups. It is also a political nation as long as you buy the bargain — the state language is Ukrainian, you understand the nature of Ukrainian history, you understand the separate path that Ukrainians took in their development, the cultural differences that emerged between them and Russia, the connection to more democratic forms of governance, some of which even have roots in the Cossack period. It was a combination of that.

Some people, presumably to this day, still retain some of these Russian sympathies, but they're a very, very small minority. It's dangerous at this point and regarded as treasonous to be calling for unification with Russia and so on. We don't hear much about that. I don't think all of them have disappeared, but it's a very, very small minority. The proof of that was polling done that the Ukrainian newspaper Zerkalo Tyzhnia published in 2014 that showed the majorities in the east and the south were very angry and opposed to the incorporation of Crimea into Russia. The vast majority did not want to be part of Russia. And that happened before the war. So, it pivoted.

In a sense, maybe it was a blessing that Putin tried to do that first through subversion. Maybe he was deceived by people like [Viktor] Medvedchuk who told him, "Just give us more money. We will build a movement on the order of what was built in Georgia "after their war of 2008. You have a government there now that can quietly reintegrate and distance itself from the West. And I think Putin fell for it. But that gave Ukraine an eight-year period from 2014 to first stave off and stabilize. Then, secondly, to build deeper support in the West. And third, to consolidate as a nation and re-up its game in the military-industrial sector and its military capabilities.

Adrian Karatnycky

Adrian Karatnycky

Adrian Karatnycky, one of the founders and Co-Director of the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council in the United States and director of its Ukraine-North America Dialogue. From 1993 until 2003, he was President of Freedom House, during which time he developed programs of assistance to democratic and human rights movements in Belarus, Serbia, Russia, and Ukraine, and devised a range of long-term comparative analytic surveys of democracy and political reform. For twelve years he directed the benchmark survey Freedom in the World and was co-editor of the annual Nations in Transit study of reform in the post-Communist world. He is a frequent contributor to Foreign Affairs, Newsweek, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, the New York Times, and many other periodicals. He is the co- author of three books on Soviet and post-Soviet themes. His latest book is Battleground Ukraine: From Independence to the War with Russia.