Looking at Ukrainian resistance through the prism of culture with Taras Filenko

Four years into the full-scale war, and with Trump trying to cut a ceasefire ‘deal’, it seems that many still don’t understand what the war in Ukraine is about. It’s not just about land, although Ukraine has vowed to recover every inch of Ukrainian territory that has been occupied by Russia. It’s not about Nato. Before the full-scale war began, the West had pretty much made it clear that Nato membership wasn’t on the radar for Ukraine.

The thing that most people still don’t get is that this is a deeply personal, cultural war. Russia is trying to erase Ukraine’s identity. Putin made it amply clear that he believes Ukraine is an ‘artificial’ country and that Ukrainians are nothing more than Russians who have ‘lost their way’. It is this blatant revision of history and forceful attempt to eradicate Ukraine that Ukrainians are fighting. This is an existential battle for Ukraine’s freedom – freedom to speak the Ukrainian language, freedom to preserve Ukrainian culture and traditions, freedom for Ukrainians to decide their own future.

Russia has tried to suppress these Ukrainian cultural elements for centuries, across the periods of both Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union. In fact, as far back as 1720, Russia’s Tsar Peter I had issued a decree banning the use of Ukrainian language in religious texts and books. Then Russia’s Catherine II ordered all churches to conduct services only in Russian language in the then Russian empire’s Ukrainian lands. In 1786, Russian became the only language of teaching in Kyiv’s prestigious Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Catherine also tried to ‘dissolve’ the Ukrainian ethnicity. Devastatingly, in 1863 a decree banned the publishing of books in Ukrainian. In fact, the Ukrainian language was derogatorily referred to us ‘little Russian’.

Further, in 1876 the restrictions were tightened, banning imports of works in Ukrainian including stage performances, public readings and texts for sheet music. In 1847, Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national bard, was arrested and exiled, and his iconic work Kobzar was banned throughout the Russian empire.

Such curbs on Ukrainian culture continued in the Soviet Union. First under the sinister garb of indigenisation where Ukrainian culture was allowed but portrayed as simplistic, rural or silly. Then came the crackdown under Stalin when Ukrainian writers and artistes were muzzled, executed or exiled. Ukrainian intellectuals were accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism’ and relentlessly persecuted.

It is this Russian imperialist impulse vis-à-vis Ukraine that continues today. Therefore, Ukraine’s struggle is naturally coded in Ukrainian music, art and literature. It is against this backdrop that Ukrainian ethnomusicologist Taras Filenko’s recent India tour opens an intimate window to Ukraine’s ongoing struggle against Russia’s war of aggression. Filenko performed concerts in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Nagaland as part of his month-long tour, providing his audiences with valuable insights into Ukrainian music, history and the war.

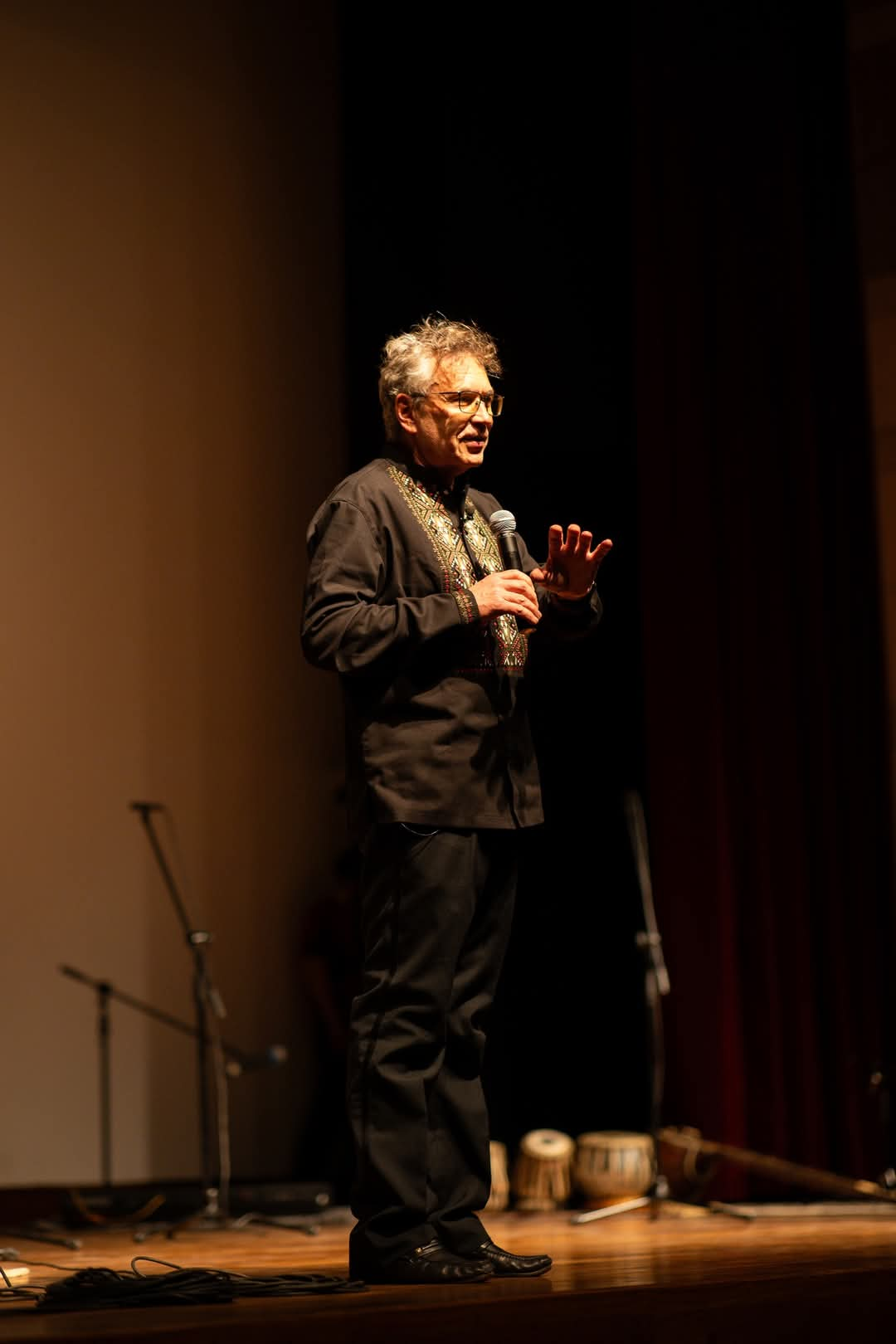

Taras Filenko performing at Father Agnel School, New Delhi

Donning the traditional Ukrainian vyshyvanka (embroidered shirt) during his performances, Filenko embodied the spirit of Ukrainian resistance. “You know, during Soviet times I couldn’t wear this vyshyvanka openly,” says Filenko. “I play Ukrainian composers wherever the opportunity arises. There was a time when Ukrainian music had almost been quashed by the colonisers. Everything was banned. It is thanks to a few great people who persevered and preserved Ukrainian music that out Ukrainian culture survived.”

In his performances, Filenko takes his audiences on both a spiritual and temporal journey, combining piano pieces by Ukrainian composers such as Mykola Lysenko and Myroslav Skoryk with moving presentations of Ukrainian art and photographs from the war.

The other strand of Filenko’s tour highlighted the comparative similarities between elements of Ukrainian and Indian music. “I was amazed by the music in Nagaland. I see similarities between Naga folk music and the music of the Ukrainian Hutsul culture from the Carpathian Mountains,” says Filenko. “The most remarkable though is the Ukrainian bandura (musical string instrument) because the bandura mode and the Indian raga mode have such similarity.”

In his grand finale performance at New Delhi’s Lotus Temple, Filenko combined Lysenko’s Rhapsody No.2 with kathak (performed by Nisha Kesari) in a dazzling amalgamation of Indian and Ukrainian cultures. This was followed by the stunning AO Naga Choir singing Lysenko’s Prayer for Ukraine, marking a high-note in Indo-Ukrainian cultural solidarity.

“As long as Ukrainian is spoken in any part of the world, the Ukrainian nation will survive,” Filenko said in one of his concerts. Given the war, the world certainly needs to stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine who are fighting for their right to exist as a nation.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author's own.

Top Comment

{{A_D_N}}

{{C_D}}

{{{short}}} {{#more}} {{{long}}}... Read More {{/more}}

{{/totalcount}} {{^totalcount}}Start a Conversation