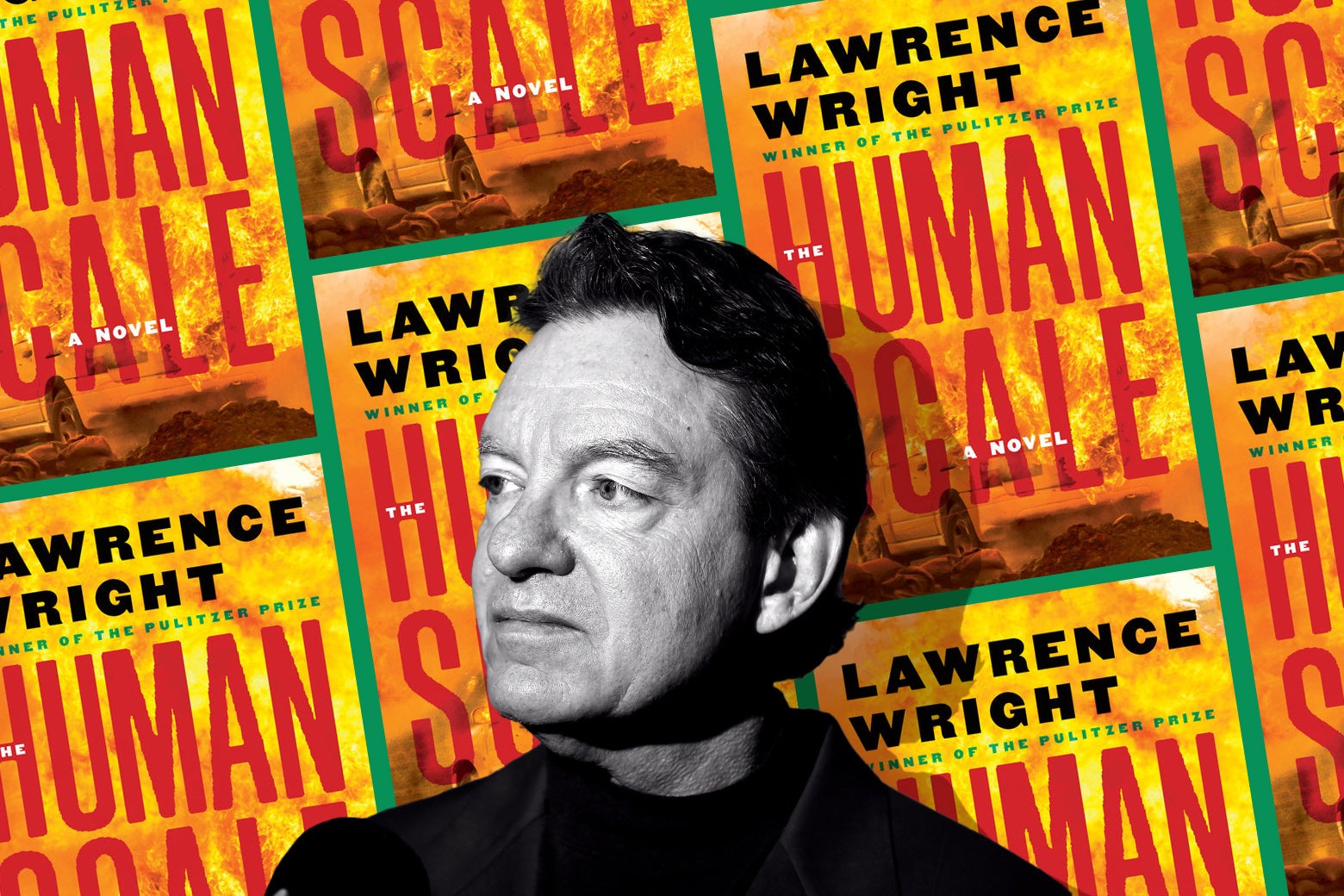

Few American writers have spent as much time trying to make sense of political violence in the Middle East as Lawrence Wright. The Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author of The Looming Tower, Wright has spent decades reporting on the violent forces that have shaped the modern Middle East. His new novel, The Human Scale, he says, is an attempt to tell the story of Israel and Palestine in a way that his reporting never could, following a Palestinian American FBI agent investigating a murder in Hebron, a city that Wright visited and describes as a microcosm of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. But in the months before the book’s release, the real-world events of Oct. 7 and the subsequent war in Gaza forced Wright to revisit his manuscript and wrestle with how his story fits into a rapidly shifting reality.

I spoke with Wright about the challenges of writing fiction about an ongoing war, the ways reporting can flatten or obscure the moral complexity at play, and the difficulty of humanizing a conflict when even acknowledging certain perspectives can feel dangerous. We also discussed his own experiences in Gaza and whether fiction can get us closer to the truth than journalism can. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Aymann Ismail: How did the idea for The Human Scale come about?

Lawrence Wright: I wrote a screenplay with this idea 20 years ago. I was working with a Hollywood producer, Robert Court, but we couldn’t get any response. So I put it aside, but I never forgot about it. Then, in late 2021 or 2022, I found myself without a project and thought, There’s one story I never succeeded in telling properly. I wanted to go back to the original idea and see if I could solve the artistic problems I had when I was writing it as a script.

As a reporter in the Middle East, I was always frustrated that I couldn’t adequately explain why this conflict was so durable, why it kept going, year after year. I’m the same age as Israel, and this conflict has lasted my whole life. And this is at a time when apartheid in South Africa ended, the Soviet Union dissolved, America elected a Black man president—all things that were never expected to happen, but they did. We had Vietnam, Iraq war I, Iraq war II, Afghanistan, and they all ended. But this just keeps going and going. So I wanted to enter the problem through the eyes and minds of characters who represent opposite perspectives, and a novel seemed like the best way to do it.

So the book begins in America, following a character who is Palestinian American. Why did you start there?

It helps to have a naive narrator who can address the gaps in understanding the reader would naturally have. But he’s also inspired by real-life FBI agents I knew, especially Arab agents navigating their own particular quandary, especially coming out of the war on terror.

I knew a lot of these people. Ali Soufan was a major source for me when I was researching my book The Looming Tower right after 9/11. Before that, I wrote The Siege with Denzel Washington, Bruce Willis, and Tony Shalhoub, who played an FBI agent. I had gone to the FBI and talked to agents, and I heard about this Lebanese American FBI agent. He was one of only seven in the bureau at the time who spoke Arabic. I wasn’t allowed to talk to him because he was undercover, but he became the model for Tony Shalhoub’s character.

After 9/11, I finally got to talk to Ali Soufan, the guy who identified the hijackers, arguably one of the most important agents in FBI history. Over time, I was able to speak with more intelligence officers who had an ethnic connection to the conflict. Their perspective isn’t one you normally encounter, and that’s where the character Tony Malik came from.

You spent years reporting in the Middle East, but you’ve said it was frustrating because you couldn’t tell the full story. What was it that led you to fiction?

My reporting always felt incomplete. I started my career covering race relations in Nashville, then taught at the American University in Cairo from 1969 to ’71, where I developed a deep fondness for the region. My students were bright, ambitious kids living under a tyrannical Arab government. When I returned as a reporter, it was dismaying to see how entrenched these regimes remained. Every time I left, I felt relief going back to a country where people could realize their opportunities. In the Middle East, that frustration often boiled over into violence, which I explored in The Siege. It was my first attempt at dramatizing what I had been reporting.

That film asked, What would happen if terrorism came to America, as it already had in London, Paris, Tel Aviv? How would our country react? It was speculation, but it was fueled by my anxiety about the rising radicalism in the Middle East. The movie experience was in some ways a bitter experience for me because it was attacked by Muslims for stereotyping Arabs as being terrorists. I had consulted with lots of human rights organizations, and when I asked, “Well, if you don’t want them to be Arab terrorists, what ethnic group would you like me to settle on?” they said, “Oh, just make it a generic terrorist.” But there are no generic terrorists. There are specific people with specific goals, and then it happens that this is the region in the world that I have some expertise and anxiety about. The theaters were picketed. It was a box-office failure. Then, after 9/11, it became the most rented movie in America, along with The Prophecies of Nostradamus. It was very strange. It became a success in the most awful way imaginable.

Does continuing to make work about the Middle East challenge you in similar ways? Do you find it difficult to reach an audience that sees your work as a creative endeavor rather than something with an agenda?

Well, you report on that part of the world. You know that it’s difficult to get people to widen their perspective and see the other as a fully realized human being with a history and with ambitions that deserve respect. It made me reflect on my first days as a reporter, covering civil rights in the ’60s. This country was torn apart. The cities were flamed. People were getting beaten on buses and at lunch-counter sit-ins, and it seemed like an insolvable problem, but it is one of those problems that America addressed. It’s not perfect, but it’s not what it was. And the question is: Why couldn’t that happen in the Middle East? It’s not as if the Arabs and Jews are doomed to be antagonists. You go to Brooklyn, you can see the same people living together quite comfortably. So it’s the context, it’s the region, it’s the history. But it’s not that they’re different people. They’re basically the same people divided by religion, but religion doesn’t need to be a divider between people.

Well, the way I understand it is that it’s not really a failure of finding peace. It’s a failure of justice. When either side sees justice as coming at the expense of the other, peace becomes impossible. That’s what I find interesting about the partnership between Tony and Yossi in The Human Scale. Can you talk about how you plotted out that dynamic?

To start with Yossi, like a lot of professional army, intelligence, or police officers in Israel, he’s a tough guy. He’s been through the wars. He’s got blood on his hands, but he justifies it because he believes Israel is the only true safe harbor for Jews, and he’ll do whatever it takes to ensure that that remains true. His parents were Holocaust survivors who made it to Israel. There are a lot of people with that same background who feel exactly as he does: threatened and angry at Palestinians. They blame them for the need to enforce security, even brutally. In their minds, it’s because of the Palestinians that Israel has to treat them this way.

Tony Malik comes at it differently. As you pointed out, he’s an American. And there’s some narrative utility in making him half American, a man who had never been to Palestine, though he had worked in the region. He’s not particularly religious, but he’s still part of the Palestinian tribe. That’s something he doesn’t fully realize about himself until he gets to Hebron and meets relatives he’s never known before. He suddenly sees that there’s an entire clan of Maliks stretching across the Middle East and he’s one of them. It’s a moment of identity for him. At the same time, he doesn’t understand why the conflict has to go on. That’s part of the education he undergoes through his relationship with Yossi.

Hebron is incredibly fraught because of how militarized the checkpoints are. Is that why you chose Hebron?

I chose Hebron because it’s often seen as a microcosm of the whole situation. It was one of the first settlements and home to some of the most radical settlers. No other city in the West Bank has settlements right in the heart of town, so the stress is right in the center of the city. I first went to Hebron in 1997 on a State Department tour of Cairo and Jerusalem, presenting the American model of publishing.

My agent, an editor, a poet, and I were going around explaining how books are published in America. But I heard there was a disturbance in Hebron and was naturally curious. Palestinian kids were throwing rocks at Israeli troops, and I wanted to see it for myself. When I got there, I saw that the rocks weren’t even making it over the building separating them from the soldiers. It was one of the most feckless protests I’d ever seen.

What struck me more was what wasn’t being reported. Al-Shuhada Street, the main market street in the old city, was still open then. School had just let out, and Palestinian schoolgirls were walking down the narrow street. Above them was a settlement, and Jewish boys were throwing rocks down at them. It was appalling. Then one of them threw a rock at me, and it really pissed me off. I had to fight the urge to throw it back. But what stopped me was seeing an Israeli soldier with an M16 standing there, protecting those boys as they tried to hurt these girls. That’s the mission of the Israeli army in Hebron—to protect a few hundred settlers with thousands of soldiers in a city of about 200,000 Palestinians. It’s densely populated, incredibly intense. When I went back to this story, I set it in Hebron because it exemplifies the conflict more fully than any other place I’ve been in the region.

Why do you think the Palestinian kids throwing rocks was seen as a disturbance but not the settler kids doing the same?

I don’t know. It was a revelation to me. News crews were there, showing images of Palestinian kids throwing rocks. But they weren’t showing that those rocks were just hitting a building. The whole thing seemed absurd to me. It was a wild contradiction, especially as a reporter. One picture was being sent out to the world, and it was nothing. A nonevent. Meanwhile, there was this appalling scene of an Israeli soldier protecting Jewish boys as they stoned Arab girls, and it wasn’t being covered.

It reminded me of my days as a race-relations reporter. That position was created to cover the Civil Rights Movement in places where local papers weren’t reporting what was happening. In the Deep South, news outlets would essentially cover things up. The race-relations reporter’s mission was to provide unbiased news to local papers that might otherwise feel threatened by covering it themselves.

How do you show balance when one set of kids is throwing stones in the direction of soldiers and hitting a building and another set of kids is raining stones on other kids from above with the backing of a militarized state?

It’s a quandary that always plagues our profession. Are you excusing? Are you ignoring? Are you engaging in “If this, then that” reporting, where everything has to be made equal? My response is to use my own judgment about what’s important to cover while acknowledging the backdrop against which these actions occur. That way, the reader at least sees where it comes from and why people might react the way they do. It’s better to address it than to simply stand on neutrality. For instance, with Kiryat Arba, I went there and got a tour from their community spokesperson. In the novel, settlers are characters. Some are part of the violent extremism that radiates out of Kiryat Arba, while others are more reasonable. I tried to balance it based on what I understood about the settlements. It’s not as simple as it seems when you’re just reading about it from a distance.

And how did that balance play into how you approached writing this book?

There are always two sides to a conflict, and as reporters, we can talk to people and look in their eyes. But we can’t look behind their eyes into their minds. A novel is the only way to do that. It’s the only artistic way to explore a person’s intellect and how their history has shaped their behavior.

That was my motivation for writing this as a novel. I’ve struggled with why this conflict endures decade after decade, so I wanted to present two characters whose experiences and histories put them in direct opposition. And yet, they have a problem they need to solve. Who killed the chief of police, and why? The reader wonders if they can work together and trust each other. Neither Yossi nor Tony Malik can solve the crime alone; they have to do it together. And if they can find a way to work together, then maybe there’s hope. But you see how difficult it is because history, ethnicity, and religion have pulled them apart.

At the end of the novel, you weave in the real-world event of Oct. 7. I assume that happened after you had already started drafting. How far along were you when that happened, and how did you decide to add it into the book?

There were a couple of inflection points in the final drafts. One was in February 2023, when I went back to the region mainly for fact-checking. By then, I had more or less written the book, but I wanted to verify details, describe buildings, check scenes with people who resembled my characters. I visited Hebron, met with settlers, spoke with a member of the Shin Bet and police officers. Basically, I sought out real-life equivalents to my characters.

One of the people who showed me around was Issa Amro. He’s, as far as I know, the only remaining peace activist in Hebron. He reminded me of civil rights figures in the U.S., the kind of people who were beaten at lunch counters or on buses in the South. I was struck by him. One of my characters is, in some ways, modeled on him, though my character makes choices Issa never would.

We were walking through the old city with a Belgian photographer named Barbara. Al-Shuhada Street, where I had witnessed the stoning of Palestinian schoolgirls years ago, was almost entirely shut down. No shops. Arabs forbidden to walk there. Issa had to take a parallel route through a Muslim graveyard. At one point, Barbara and I reached a checkpoint manned by a young Israeli soldier, maybe 18 or 19, fresh out of high school. A handsome kid, but clearly policing a very tense environment without the maturity to handle it. He checked our IDs, saw we were Westerners, and realized Issa was with us on the other side of the wall. When Issa caught up, the soldier rushed toward him. Barbara filmed the encounter.

Issa knew the rules and kept insisting, “Call your commander. He’ll tell you this is legal.” The soldier radioed in and said, “I got a bunch of liberals here.” I joked, “Wait, I’m from Texas,” but that didn’t matter. He shoved Issa onto a bench, stood over him knee to knee with his M4 hanging inches from his lap. It was extremely menacing. Other soldiers were watching from a barracks across the street. I went over and said, “This is going south. You have to pull this guy back.” They didn’t move. I could tell they were afraid of him. He was hotheaded. Not long before, a Palestinian had been shot or beaten unconscious nearby, and an Israeli soldier walked up and executed him right there.

Wow.

I was worried how this would end. Then, out of nowhere, the soldier grabbed Issa by the neck, lifted him off the bench, threw him to the ground. His head missed a curb by an inch. Then he wound up and kicked him so hard he almost fell over himself. No one intervened. But then a man in a red sweatshirt, whom I took to be intelligence, stepped in and shooed the soldier away. Even then, the kid kept circling, like he wanted to go back and finish it. I’m pretty sure that if Barbara and I hadn’t been there filming, he would’ve killed Issa. And what shocked me most was that it didn’t matter that we were witnesses.

It made me rethink my manuscript. I’d turned in my first draft in August 2023. Then, two months later, came Oct. 7. That was a quandary. It was such a deep wound in Israel, and I knew it would be sensitive to write about. I’d felt the same when writing about 9/11. It was such a tragedy, with so much grief and anger, that even addressing it felt like exploitation. The first draft of my book ended with a war—one of those Israeli military campaigns where they go into Gaza, level some buildings, then retreat and let Hamas rearm and rebuild until it happens again. That’s what I expected. But the real thing, what actually happened, was so much bigger and more tragic.

At that point, I had choices: I could set my story earlier in history or imagine a future scenario. But I felt I had to address it head-on. I’d been writing around this conflict for so long, and I thought the real challenge was to go right into it and make it more real to the reader than news reports or TV clips. To set it in the lives of two characters the reader has come to care about. That felt like the only honest way to handle it.

One thing I’m sensitive to as an Arab American reader is how often we pause to analyze why the most extreme Israeli actions happen and why militarized apartheid exists as it does, while the same level of empathy is rarely extended to militant Palestinians, who unquestionably experience immense trauma and cruelty, like the example of the “handsome” hotheaded soldier you just pointed out. Especially in today’s political climate, where humanizing armed Palestinians feels like it could get someone deported, I was curious to see how you’d approach it. Yet, in your book, you describe Israeli soldiers as kids and Hamas as terrorists. Since your goal is to humanize the conflict, how did you navigate that balance in portraying everyone involved?

I had an experience with Hamas. It’s kind of embarrassing. I was in Gaza in 2009, right after Operation Cast Lead. This was when Hamas had kidnapped Gilad Shalit and held him for five years. The Israelis never found him, and eventually, they traded him for a thousand Palestinian prisoners. To me, that was the origin of this story, which revolves around the question of how one life can equal a thousand. That trade suggests an unbalanced valuation of human lives in this conflict, which is at the heart of why this war feels so impossible to resolve.

At the time, Gaza looked utterly destroyed—though, of course, not like what we’re seeing now. I had an appointment with Khalil al-Hayya. It was July, and it was sweltering, and there were all these kids in Hamas summer camp in a schoolyard wearing these little green beanies and handkerchiefs in Hamas green, and the leaders of Hamas were sitting in folding chairs watching these kids sing. But while I was sitting with them, I started feeling ill. The night before, I had gone to a restaurant on top of my hotel. Looking out at the Mediterranean, I saw the waves were thickly green because the sewage treatment plant had been bombed and wasn’t working. So I thought, Well, I’m not ordering fish. So I ordered a steak. I’m thinking of the cattle that they were bringing through the tunnels at the time. The waiter asked if I wanted it “well done or very well done,” and somehow I missed the hint. The next day, it had caught up with me.

I was trying to put on a brave front through this interview with al-Hayya, but I wasn’t doing a very good job. I’m interviewing him in front of a group of his colleagues and subordinates. It felt kind of Oprah-ish. He was a forthright, interesting interview. He had already lost one child to Israeli bombing, though that wasn’t what led him to Hamas. Shortly into the interview, I realized I was going to faint, and I kind of fell. Out of nowhere, they brought out a mattress—who knows why there was a mattress in a school—and covered it with prayer mats. I crawled onto it and kept the interview going, flat on my back, surrounded by the dusty boots of Hamas fighters. As humiliating as that was, he was very kind to me. He left an impression. And now? He’s the leader of Hamas. He replaced Sinwar. The man I was talking to while lying on my back was one of the key planners of Oct. 7.

So how do you reconcile that?

That became a real challenge because, as a reporter—but especially as a novelist—you have to paint your characters in dark and light colors, and this was a vivid example of that. I don’t know if I succeeded from your perspective, but having been in Gaza and seeing how Hamas treats its own people, that’s something that doesn’t get reported much. In some ways, it’s not much different from other forms of tyranny in the Arab world, but it is a terrible government. The West also tends to take a broad brush with Hamas, assuming that everyone holding a position in the government is a full-fledged member of Hamas, when in reality, membership is almost required for many public roles. For example, in Operation Cast Lead, the first thing the Israelis did was bomb the police academy during a graduation ceremony. Were the graduates Hamas members? Technically yes, but only because you had to be if you wanted to be a policeman. There’s a lack of distinction in how the conflict is viewed, a kind of blindness to the nuances of the environment. For instance, it’s often said that Hamas hides among civilians. That’s true. But it’s also true that Gaza is 20 miles long, 7 miles wide, and home to 2 million people. Where else can they be? Failing to make these distinctions excuses behavior that might otherwise be moderated.

It’s difficult for me, especially as an Arab American, because I can’t help but humanize people who look like me, speak the same language as me, and have kids with the same names as mine. I have this hang-up where, if someone describes “the barbarism of Hamas,” I also hope they’d acknowledge that a policy of “mowing the lawn” in a densely packed, closed-off enclave is also barbaric, especially when civilian infrastructures like sewage treatment plants are deliberately bombed.

I realize we’re moving a bit beyond the book, but it seems as if you’d agree that one of the challenges of writing about this conflict is how deeply personal it is for so many. How do you account for readers coming to this from drastically different perspectives from your own while drafting?

That’s actually the whole point. In some ways, you as a reader are my object. My hope is that something in this novel opens your eyes to a different perspective and maybe pulls you away from automatic reactions, even if only a little. I am sure that I haven’t succeeded in this regard, but to try to appeal to a reader like you by presenting the Israeli perspective in a way that might be more digestible, that’s a big part of my goal. And it works the other way too. I know that Oct. 7 is an incredibly deep wound in Israeli society, and for some it’ll be too painful to read about. Just as, for you, it’s frustrating when the trauma in Palestine isn’t given the same attention as the trauma in Israel.

But anyway, however much I’ve succeeded or failed, that was my objective.