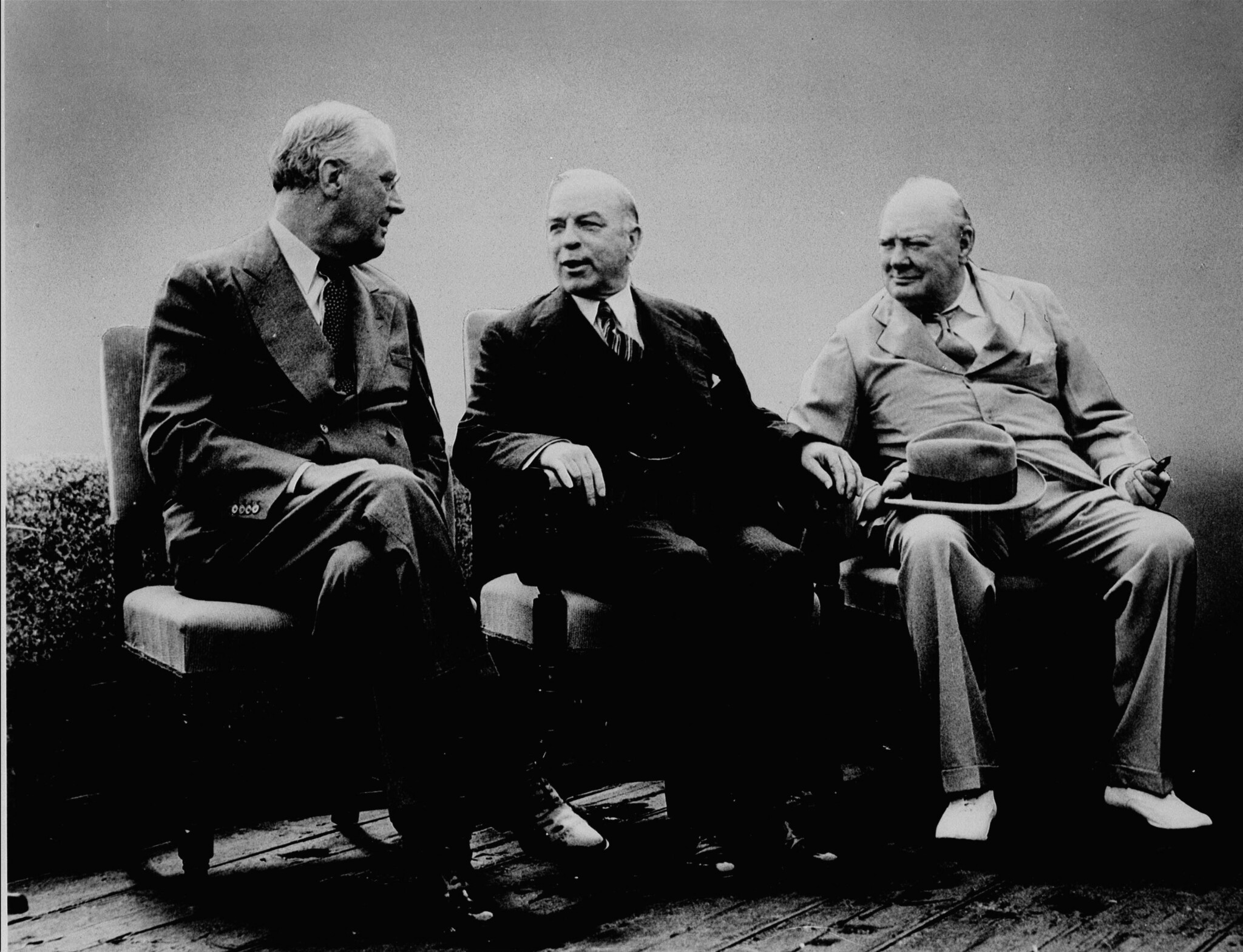

In this week’s Hub book review, Lydia Perovic examines The Third Man: Churchill, Roosevelt, Mackenzie King and the Untold Friendships That Won WWII (Sutherland House, 2021), which explores the crucial diplomatic role William Lyon Mackenzie King played as a go-between for the U.S. and Britain during the Second World War.

In the first part of the Second World War, when the officially neutral U.S. and its president, hampered by an isolationist Congress and neutrality law, couldn’t be seen cooperating in any way with a belligerent country, Canada and its long-serving PM Mackenzie King played a crucial role as the most reliable communication channel between Roosevelt and Britain. Even after Roosevelt established secret correspondence with Churchill, and right through the war and the eventual American takeover of the war command and after V-E Day, King remained a factor. Canada was not necessarily consulted on war strategy, but King traded agreeableness for access—and for the all-important intel for personal use and for posterity: neither of the great war leaders knew that King kept a detailed diary in which he recorded almost everything shared with him in confidence.

Neville Thompson in The Third Man: Churchill, Roosevelt, Mackenzie King and the Untold Friendships That Won WWII (Sutherland House, 2021) makes ample use of the diaries and also fact-checks them against other published records and the decades that have lapsed between our time and theirs. Thompson is a delightful guide: witty, deadpan, keeping a close eye on the Brahmin men who held the fate of the world in their hands.

And the three men did get along, though it took King some time to warm up to either. Early in his acquaintance with Roosevelt, he was highly skeptical of the New Deal but was soon won over and defended Roosevelt against the criticism of the “moneyed interest” whenever possible.He continued to believe that free trade and tariff elimination are something of a panacea for all the world’s ills and that the post-Depression economies would just need to heal on their own even as he introduced the first elements of the Canadian welfare state himself.

Churchill took a longer time warming up to. King’s favourite British PM was the Conservative Stanley Baldwin, whose cautious approach and lack of grandiosity he trusted implicitly. As the popular historian-podcaster Dominic Sandbrook recently wrote in his fan letter to Baldwin, while there will always be questions about his reluctance towards rearmament, “Baldwin’s contribution to victory was arguably deeper and more important. Thanks to him, Britain entered the war united—perhaps the greatest asset of all.”

Exactly this was the order of the day for Mackenzie King as well, who leading up to and during the war tried to keep the country united, with Conservatives advocating for stronger commitment to the empire and demanding conscription, Quebec adamant that it would accept no such thing, and a likely CCF electoral victory in the wings if the government fell on this question. Until the very last year of the war, King managed a substantial Canadian war effort without conscription, and when it was finally introduced, volunteers and redeployed experienced troops replenished most of the required forces.

Not even after Poland was invaded would King accept Churchill’s view of the situation in Europe, or see the urgency of overseas deployment. Churchill was an anomaly among European and British political figures, considered a blowhard, a warmonger, presumed unaware that another world war would bring an end to civilization. But Churchill’s historical clarity and outstanding oratory won over first Britain, then the free world.

Canada started by deploying destroyers and RCAF pilots and aircraft. The Britain-stationed ground troops trained and trained and remained unused for a long time, and there was grumbling about boredom and lack of purpose. And while King did his best to carve out Canadian independence from the empire—while confirming its undying loyalty to Britain itself—the first big engagement and loss of life (counting hundreds) was in the British colony of Hong Kong. The second was the tragedy of Dieppe in 1942, a too-early, poorly organized attempt at Allied landing on the shores of Nazi-occupied France which resulted in more than 900 Canadian deaths. (This did not harm Mountbatten’s career. Churchill’s favourite and a relative of the Royal Family failed upward, as we now say.) Canadians were back, and successfully, in the battlefield for the Italian leg of the Allied reconquista of Europe, and of course on D-Day.

The country’s role as a sober diplomatic middleman was almost equally important. When Britain cut diplomatic relations with the Vichy government, Canada maintained its own and made the most of it on behalf of the Allies.The question of whether Petain would let the Germans take over French military assets, crucially the French fleet, or if he’ll try to keep it all parked and wait till the Allied invasion was a major issue in military planning—as was whether to recognize de Gaulle as the legitimate leader of France and when to do so. Roosevelt and Churchill held two conferences in Quebec City, and otherwise either travelled to King or had him over multiple times a year. King was a regular in official residences, alternative residences and cottages, and got along gloriously with both Eleanor Roosevelt and Clementine Churchill.

He felt a more natural affinity with the American president, but felt more duty-bound to Churchill, while also disabusing him of his fantasies of a more centralized empire. (Churchill, King noted drily, used “commonwealth” and “empire” interchangeably, while King made every effort to remind him of the difference between the Dominions, colonies, and India.) Roosevelt, with preparations for the creation of what would become the United Nations underway, had no truck for any notion of the British Empire colonies continuing as such, and this displeased Churchill. But the three men and their leadership teams worked across their differences.

The book is full of fascinating characters and cinematic scenes, many involving diplomatic, administrative and military staff, family members, friends, and “special friends.” (Were any marriages in the Anglo upper classes monogamous? Unclear.) Churchill, predictably, gives the best copy. Photographer Yousuf Karsh in Ottawa snaps the cigar from his mouth—and the man himself out of the grumpy state—to take what will become the most iconic photograph of the statesman.

Whenever he visits Roosevelt, Churchill flips night for day, sleeps in and works from bed, stays up later than anyone, drinks and smokes inordinately, and evinces a flexible notion of propriety.Alas, it isn’t true that he greets Roosevelt in his room naked on one occasion while saying “The prime minister of Great Britain has nothing to conceal from the president of the United States” though he did greet him clad in nothing but a towel. Unlike many of his peers who had stable inherited or family wealth to prop their careers in politics, Churchill was a freelance writer of books and journalism, coming treacherously close to bankruptcy and almost abandoning politics altogether in the 1930s.Was Churchill one of those precarious wealthy people, I asked Neville Thompson via email. Were there no sinecures, properties to rent, inherited money? “The best book” he writes back, “and it is a very good one, on Churchill’s finances is David Lough, No More Champagne (2015)… He says that he never met anyone who took such risks as Churchill. He made a lot of money as a prolific writer but lived at a very high standard—almost always in debt, and sometimes seriously so—and gambled much away at French casinos and on stock markets. He was not above getting huge advances and not delivering the manuscript for years, if ever. […] After WWII Churchill had plenty of money, though Clemmie, a good spender herself, was a bit pressed by such lavish standards. He did not inherit much since his father, who was not a wealthy aristocrat, also lived too well and his widow (whose next two husbands were Winston’s age) even more. There were no lucrative sinecures.”

He was physically free, with an almost toddler-like abandon. King’s diary recalls a late night when, after quite a bit of drinking, Churchill grabbed him and waltzed him around the room. My favourite scene though must be King going to bed early and leaving Churchill behind to work on a speech, then waking up at 1.30 a.m. and hearing him singing to a gramophone. Came the hour, came the man. And also, notably, came the tune, came the man.