This is Part Three of a series on the Lord’s Prayer; go to these links for Parts One and Two.

καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν, ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφήκαμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν·

[kai afes hēmin ta ofeilēmata hēmōn, hōs kai hēmeis afēkamen tois ofeiletais hēmōn:]

also release to-us the debts …….our, ….as also .we have-released the ..debtors …our;

And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us.

This is the appropriate clause for confessing one’s sins in prayer; it is also the right place for intercessory prayers for those who have sinned against us (whom we are under direct, explicit orders to pray for).

The verb translated “to forgive,” ἀφίημι [afiēmi], is far broader in Greek than it is in English. Its base meaning is “to release, let go of,” from which it derives many, sometimes contradictory, extended meanings. These include: “to emit, send forth”; “to disband, break up, dismiss, dissolve”; “to lose, throw away, forsake, abandon”; “to forgive, absolve, excuse, pardon, remit”; “to divorce”; “to permit, allow”; “to set free, manumit”; and “to set sail.” It is, accordingly, one of those words that tends to defy my preferred philosophy of translation!

It occurs here in the imperative form, ἄφες—and I’m not even going to try to analyze the divinely-commanded audacity of commanding God to forgive us!—and then a second time, in the form ἀφήκαμεν. This latter is what’s called a present perfect verb, denoting an action that’s been completed but is still relevant in the present; a favorite illustration of this in English is “I have eaten,” which implies that you’re done but are still full. “Forgive us as we have forgiven,” almost as if we have just now done it (which may indeed be literally the case): The idea seems to be that, in praying this, we hereby pardon those who have sinned against us, approaching the Throne and formally or officially renouncing our claim against them.

I said in my last that this is the most neglected, even the most hated, clause of the Our Father. That calls for some discussion.

An Excursus for Our Times

Illustration (ca. 1115) of Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV begging Abbot Hugh of Cluny and

Margravine Matilda of Tuscany to intercede

for him with Pope Gregory VII.1

In Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis says (with a simplicity that belies the bite of his words) that “Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea, until they have something to forgive”. Further, he goes on to correctly pinpoint why most of us find forgiveness so hard: namely, that most of us, most of the time, find the idea that we should forgive not so much difficult as despicable.

We will return to the bad reason we can have for despising forgiveness later in this post. First, it must be conceded that this outrage is not always wholly unreasonable, nor always wholly unchristian. This is due to a very horrible fact, which in one context especially has been confronting the public for over twenty years now: Bad actors can twist forgiveness into an obscene parody of itself. These perverted uses of absolution can occur both between individuals and on the societal level (many non-solutions to racism rely on cheap parodies of forgiveness, for instance).

In particular, invoking compulsory forgiveness is a typical tactic employed by spiritual and sexual abusers. They frequently appeal to what they call “forgiveness” as a way to escape consequences; they are also apt to use it as a means of keeping a favorite victim available. In reality, what abusers want from this is not to be forgiven—a process which is incomplete without repentance on their part2—but to be indulged, without forgiveness. And by “indulged,” I mean “granted an indulgence,” in the theological sense.3 This term calls for some unpacking.

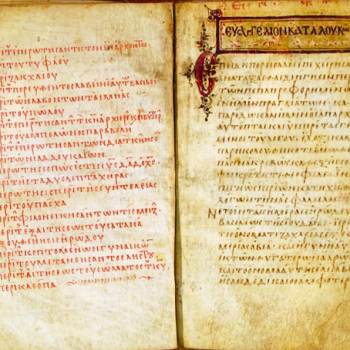

Satan Distributing Indulgences,

an illustration from a Czech manuscript

created in the 1490s.

An indulgence is being let off some or all of the natural, just consequences of one’s behavior. Say you broke a friend’s window in the course of a heated argument. It would obviously be right to both apologize and pay for the repair. The latter is, strictly speaking, your legal responsibility, and if you are genuinely sorry for what you’ve done, you will want to make it up to your friend; meanwhile, the apology (hopefully) mends the relationship that shattered with the glass. Now, if your friend forgave you and then decided to waive payment for the window, that would be an indulgence. Yet it’d send quite a different message if your friend said nothing in response to your apology, and then, when you tried to cover the cost of the window, told you “Don’t bother.” The act (not taking your money to repair the window) may be materially the same, but its effect on your relationship is completely different, depending on whether you’ve been forgiven or not.

Now, we actually know from everyday life that God often grants us indulgences. We “get off light” after confessing our sins and errors all the time. The Catholic Church teaches that, since she has the full power of the keys—whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven—she also has the authority to grant indulgences to the faithful.

However, because of how indulgences inherently work, independently of the Church’s authority, valid ones can only be granted for sins that have been absolved already. Getting an indulgence (or maybe it would be better to say, a pseudo-indulgence) instead of being forgiven is simply impossible; as the broken window analogy suggests, experiencing neither forgiveness nor consequences makes our situation worse in the long run, not better. It follows that any priest who has claimed to be giving out indulgences or pardons or anything of that sort, sans repentance, has been either stupid or lying—and Johann Tetzel was not the only or even the first fool with the word “indulgence” on his lips in Christian history. It also follows that, although abusers may deploy the language of forgiveness, that is really not what they want. What they want is the chance to smash all the rest of the glass in the house.4

Christ in the Wilderness (1872), by Ivan Kramskoy.

That such behavior should poison the very idea of forgiveness in some people’s minds is horribly predictable. It is also, if we believe what the Church claims about herself, a tragedy of the first order. It is perfectly true that the problem here is with human beings, not with forgiveness; however, we are often a little too eager to urge that fact upon others. We aren’t wrong to long for others to enter, or to return to, the embrace of the Church—but so do Christian abusers. Why wouldn’t they? That’s their hunting ground.

Which is another reason pardon is sometimes perceived not as a gift, but as a cudgel. To realize how abuse manipulates forgiveness, and then do nothing but tell the wounded to forgive because it’s not really the Church’s fault, is to make oneself an accessory to abuse.

Therefore say unto the house of Israel, “Thus saith the Lord God; ‘I do not this for your sakes, O house of Israel, but for mine holy name’s sake … And I will sanctify my great name, which was profaned among the heathen, which ye have profaned in the midst of them; and the heathen shall know that I am the Lord,’ saith the Lord God, ‘when I shall be sanctified in you before their eyes. For I will take you from among the heathen … and will bring you into your own land. Then will I sprinkle clean water upon you, and ye shall be clean: from all your filthiness, and from all your idols, will I cleanse you. A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you: and I will take away the stony heart out of your flesh, and I will give you an heart of flesh. And I will put my spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes …

“‘Then shall ye remember your own evil ways, and your doings that were not good, and shall loathe yourselves in your own sight for your iniquities and for your abominations. Not for your sakes do I this, saith the Lord God, be it known unto you …'”

—Ezekiel 36:22-26, 31-32

There are two lessons we need to take from this. The first is the crucial importance of combatting abuse within the Church. That, frankly, is a post in itself, which I may or may not write at some later time.

The second—which, incidentally, is a critical element in the first—is something we need to remember about mere justice and decency as the underpinning of forgiveness. All Christians are “under orders” to forgive; but, in any concrete situation where there’s an offense to be forgiven, the person who committed the offense literally has less right than anyone else on earth to bring up that duty to the person they have injured.

In a lesser way, this even applies to any evangelistic or apologetic conversations we have. I imagine that most people reading this haven’t committed spiritual or sexual abuse against anybody. That’s great! Keep it up. But when speaking to or about victims of abusive clergy, we need to keep in mind that for the vast majority of people, there is no meaningful difference between the Church and her representatives, of whom the clergy are, quite naturally, pre-eminent. (It may be reasonable for us, who have accepted that the Church is what she claims she is, to be deeply convinced of the difference. It does not in any way follow that we may reasonably expect or demand that others who do not accept the Church’s claims about herself should go on to draw a conclusion they have no premises to justify.) Insofar as we are bold to evangelize or do apologetics, we take on the mantle of “representatives of the Church”; to that same extent, we must not avoid or trivialize things her other representatives have done. To minimize evil that way is an offense of its own—especially, though not solely, because it is a scandal.

Pardoners’ Tales

But let us resume our main analysis. Once we have begun at least attempting to forgive (spurred, maybe, by one of the Lord’s more frightening parables), there are other traps to watch out for.

A 13th-c. illumination of St. Thomas Becket’s

martyrdom, which occurred in Canterbury

Cathedral in 1179 at the hands of four knights.

“The last temptation is the greatest treason, / To do the right deed for the wrong reason.” T. S. Eliot put that line in the mouth of St. Thomas Becket in Murder in the Cathedral. The soon-to-be martyr utters it after being visited by four tempters: The first three offered worldly comfort, security by kowtowing to the king, and security by controlling the king; the fourth offers the glamor of being a martyr, and this is the only one that nearly breaks Becket. Eliot’s friend Charles Williams wrote:

Pride is the besetting sin of Pardon … It is the condescension, the de haut en bas element, which is with so much difficulty refused. After all, if one has been injured, if one has suffered wrong? “Cast thyself down,” the devil murmurs, “the angels will support you; be noble and forgive. You will have done the Right Thing; you will have behaved better than the enemy.” So, perhaps; but it will not be the angels of heaven who support that kind of consciousness, unless by a fresh reference of ourselves to Forgiveness. “Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.”

—The Forgiveness of Sins, Ch. V: Forgiveness in Man

Nor is this the only kind of counterfeit forgiveness being peddled in Vanity Fair. In my adolescence and earlier adulthood (I feel like I see them less often now), I used to see essays by the score—secular and even professedly Christian—recommending “forgiving” others as a way to achieve peace of mind and resolve stress. This is like recommending a person be baptized because it’s a great way to moisturize. Forgetting an offense for the sake of your own peace of mind is many things, including “defensible”; but what it isn’t is forgiveness. Grace will not be thus used.

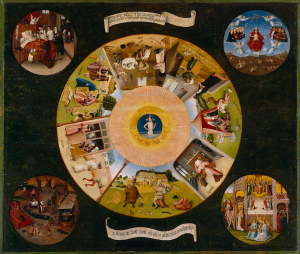

The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things

(ca. 1500), by Hieronymus Bosch. Christ

resurrected is in the center, the seven sins encircle

him, and the four last things are in the corners.5

To be forgiven, to want forgiveness, can also be tough. Sometimes this is because it is difficult to believe that something we have done is wrong—a difficulty which can often, albeit not always, be overcome by imagining how we would feel if we exchanged places with the target of our action.

But there is another difficulty in this sometimes, one that’s harder to articulate. Those of us who were raised to be, in a word, embarrassed to receive gifts and favors6 may be troubled by this problem, which is that it can feel strangely ugly to be pardoned. I have a hunch that this is the obverse of the condition Flannery O’Connor describes in the opening chapter of her first novel, Wise Blood:

His grandfather had traveled three counties in a Ford automobile. Every fourth Saturday he had driven into Eastrod as if he were just in time to save them all from Hell, and he was shouting before he had the car door open. … They were like stones! he would shout. But Jesus had died to redeem them! … (The old man would point to his grandson … He had a particular disrespect for him because his own face was repeated almost exactly in the child’s and seemed to mock him.) Did they know that even for that boy there, for that mean sinful unthinking boy standing there with his dirty hands clenching and unclenching at his sides, Jesus would die ten million deaths before he would let him lose his soul? …

The boy didn’t need to hear it. There was already a deep black wordless conviction in him that the way to avoid Jesus was to avoid sin.

It is against internet law to mention Flannery

O’Connor without accompanying peacocks,

I forget why. Photo by Mallory Cessair, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Unfortunately, what to do about this condition—this reluctance to accept forgiveness because it feels indecent—isn’t a question I have an answer to. It’s a form of pride, I know that much; both mysteriously and comically, it reverses St. Paul’s maxim: That which I allow, I do not.

The Usual Suspect

But, whether or not we indulge ourselves in any of these knottier things, I dare say most of us have the same problems with forgiveness that, well, most people have. We do not want to pardon injuries. They hurt. We would like some revenge, please. We will, many of us, be reasonable about it. Expressed in monetary terms (as, in fact, a “debt”), we’d like our own agony put back on them, ideally with interest—not usurious interest; enough to count as reasonable damages for pain and suffering, you know; and yes alright, now that you mention it a little extra would be nice, just to show them what’s what.

The Parable of the Wicked Servant

(ca. 1620), Domenico Fetti.

Unluckily for our immensely reasonable, oh-so-impartial selves, this is one of the few desires to which the New Testament quite simply gives no quarter whatever. It is not to be tamed or postponed or tempered; its merest inklings are to be given the Psalm 137 treatment: Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones. We are to forgive, and to forgive everything, and to forgive utterly. This is where the word “as” that I drew attention to in the first post of this series comes back—and this time, it comes in its full terror:

Forgive us as we forgive.

Whatever kind and degree of forgiveness we extend to others, that is precisely the kind and degree of forgiveness we are invited to ask of God. This makes sense, when you come to think of it: How else could forgiveness be just?

A Throne holding scales in the rood screen7

of St. Michael’s in Barton Turf, Norfolk,

England. Photo by Martin Harris, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Granted, it is counterintuitive to describe something that is by definition a gift (it has “-give” right in it) as something we are bound to bestow. But I believe the secret of why we need to forgive in order to be forgiven lies in this. Think of it as two economies. One operates in terms of debt and repayment, duty and punishment; the other operates in terms of gift and “paying it forward,” supererogation and amnesty. Obviously the latter economy only makes sense once we have experienced the former, but also, anyone who leaves the former for the latter must really leave the former. If we invoke the laws of the economy of debt, we shall have them—but it is of the nature of debt to exact everything we owe.

The quality of mercy is not strain’d,

It droppeth as the gentle raine from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest,

It blesseth him that gives, and him that takes,

‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest, it becomes

The thronèd Monarch better then his Crowne.

His Scepter shewes the force of temporall power,

The attribute to awe and Majestie,

Wherein doth sit the dread and feare of Kings:

But mercy is above this sceptrèd sway,

It is enthronèd in the hearts of Kings,

It is an attribute to God himselfe;

And earthly power doth then shew likest Gods

When mercie seasons Justice.

… in the course of Justice, none of us

Should see salvation: we do pray for mercie,

And that same prayer, doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercie.

—William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice IV.18

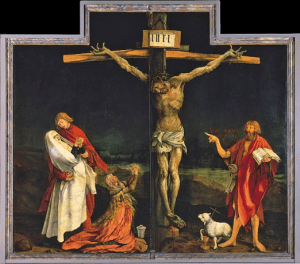

Isenheim Altarpiece (1516),

by Matthias Grünewald.

Footnotes

1This is in connection with the Humiliation of Canossa, an event during the Investiture Contest, of which you’ve likely heard if you’ve read some Medieval history. Pope St. Gregory VII, one of the great reforming popes, had a dispute with Emperor Henry IV over whether the empire or the Church had the right to invest bishops (investiture being their formal installation into office, including the reception of the material symbols of their office, such as the pallium). St. Gregory excommunicated Henry in 1076; the following year, the emperor, clad in rags in the midst of the winter snows, approached His Holiness to beg for forgiveness at Canossa (a fortress in northern Italy at which the pope was staying as a guest of Margravine Matilda—margrave and margravine in Imperial usage equate with the English marquis and marchioness). The event left a strong cultural impression: St. Gregory VII’s eventual canonization so incensed Charles VI (the fortieth Holy Roman Emperor and twelfth from the House of Habsburg), he would not allow the decree to be published in his domains … six hundred and fifty-one years after the Humiliation took place. Like, damn, House of Habsburg, maybe have any chill at all and see if that improves your relationship with the papacy?

2Forgiveness can be available to people who have not (yet) availed themselves of it; with respect to God’s forgiveness, this is the case with anyone and everyone living who is at the present moment guilty of impenitent sin. In that respect, forgiveness is not unlike marriage: if only one spouse has vowed to belong to the other, no marriage has been effected between them, no matter how willing to marry that party may be.

3Well, I do and I don’t mean it in the strictly theological sense; as we’re about to discuss, “an indulgence without forgiveness” is strictly a nonsense phrase in Catholic theology—like asking for a square without corners.

4Incidentally, this is also why indulgences granted by the Church are always attached to some kind of good work. It is important that we don’t miss out on the medicinal quality consequences can have, and so the good work in question is intended to get us that “medicine” by another means.

5More specifically: in the very center, the figure of Christ is accompanied by the sentence Cavē, cavē, dominus videt (“Beware, beware, the Lord sees”). The sevenfold circle around him, beginning from the bottom and moving clockwise, covers Īra (wrath), Invidia (envy), Avāritia (avarice), Gula (gluttony), Acēdia (sloth), Luxuria (lust), and Superbia (pride). The four circles in the corners, beginning in the upper left and also moving clockwise, depict death, judgment, heaven, and hell. At the top and bottom, a pair of scrolls read Gēns absque consiliō est, et sine prudentiā and Ūtīnam saperent, ut intelligerent, ac novissima providērent, or “It is a nation lacking counsel, and without prudence” and “If only they were wise, so that they understood this, and would consider their lattermost end.”

6I love you, Mama!

7The rood screen at St. Michael and All Angels’ Church is a rare example of an English rood screen which survived the iconoclastic measures taken during certain phases of the English Reformation.

8It’s possible that those who are pleased to call themselves “based” (or whatever the word may be by now) will be inclined to point out, smugly, that I skipped the bit of this speech which has some fairly blatant anti-Semitic language in it, and aren’t I just picking and choosing what I like from great authors, etc. However, I chose to omit that segment for a good and relevant reason: namely, that I dislike it for a good and relevant reason (because anti-Semitism is Bad Actually and Shakespeare was wrong to harbor that attitude), while he was at the same time correct to value mercy and wrote of it very beautifully here. I am the more bold to pick and choose in this fashion, since Shakespeare was an ordinary human being, capable of mistakes both innocent and culpable—not a divinely inspired prophet.