March Madness: The Northeastern Professor Vs. the Sports Betting App

Richard Daynard fought Big Tobacco in the ’90s and won. But as he sets his sights on DraftKings's ads, has the longtime legal crusader finally met his match?

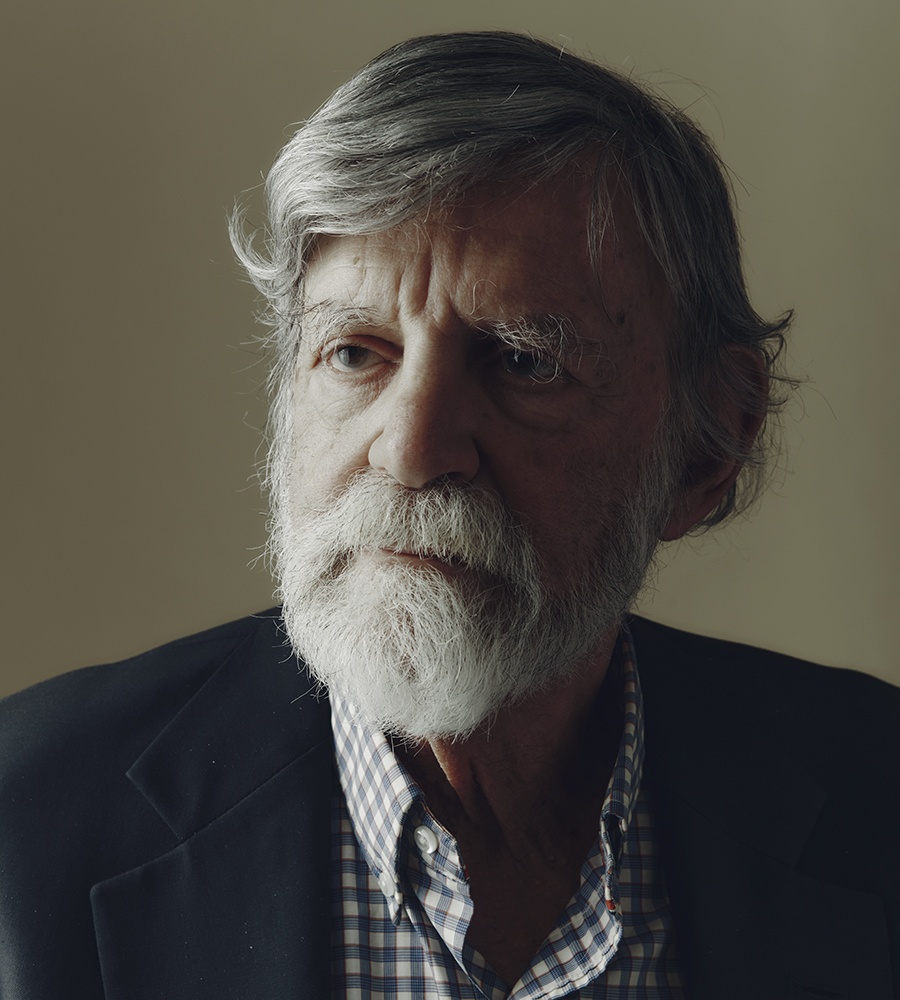

From his Northeastern law office, Richard Daynard chose academia over Wall Street, wielding the law to advance public health. / Photo by Tony Luong

Even if he didn’t realize it, Richard Daynard had taken a risk. On a warm Friday night, the Northeastern University law professor stood in the dark threshold of Banners Kitchen & Tap wearing sporty oxfords, khakis, a pastel-peach shirt, and—most conspicuously—a sweater looped around his neck. The outfit might have felt at home on a sunset sail around the harbor, but here in the palatial sports bar at the Hub on Causeway, he stuck out as an easy mark. Sure, the place has plenty of room for sports fans of all stripes, but it’s still a sports bar. In Boston. Which means a few well-lubricated patrons might not have hesitated to take a shot at the guy who looks like he uses “summer” as a verb.

Daynard didn’t just look out of place—he was a genuine stranger in a strange land. Despite living and working in Boston for more than five decades, the octogenarian has only recently begun paying attention to his hometown’s favorite obsession (other than politics and revenge). He doesn’t know a field goal from a free throw, let alone the unwritten rules of sports-bar etiquette, yet none of that has stopped him from taking on one of the most powerful forces in the sports world: online betting.

At the helm of Northeastern’s Public Health Advocacy Institute (PHAI) and its nonprofit law practice, the Center for Public Health Litigation, Daynard’s latest target is DraftKings, a publicly traded Boston-based online sportsbook with a market cap north of $20 billion. The center filed a class-action lawsuit in December 2023 against the betting-app operator, challenging a promotion that promised new users a $1,000 sign-up bonus. (Read the complaint here.) The lawsuit—which continues to wind its way through court—alleges DraftKings created an “unfair and deceptive” campaign targeting novice bettors who were “extremely unlikely to understand the details of the promotion”—even if they could read the fine print. Making matters worse, the lawsuit argues, is “the addictive nature of the underlying product.” DraftKings, meanwhile, has pushed back, maintaining in court documents that the promotion’s terms were spelled out in “easily understandable language.”

Before filing the lawsuit, Daynard, like any good academic, had immersed himself in the scholarly literature, studying gambling’s links to substance abuse, suicide, and other health risks. But the world of sports betting—and even sports itself—remained foreign territory. His colleagues were still teaching him how betting apps had transformed phones into pocket casinos and how wagering had become woven into the very fabric of watching games.

And so it seemed a field trip to Banners was in order. Under a constellation of TV screens, customers watched the games unfold in real time while betting odds scrolled on a ticker just below some of the action. As Daynard craned his neck to take in the simultaneous broadcasts, he saw how the combination of live sports and instant betting could become intoxicating.

“I think I get the idea,” he quipped as we settled into a booth.

Joining us were two of Daynard’s colleagues: Harry Levant, a former compulsive gambler turned counselor, and Mark Gottlieb, executive director of PHAI and one of the lawyers leading litigation on the DraftKings case (he’s also Daynard’s former student). As Levant explained the maze of betting options available to players, he discreetly pointed out patrons he sensed were placing wagers on their phones.

For Richard Daynard, filing a lawsuit was just the opening shot in what promises to be a long war.

For PHAI, the DraftKings lawsuit was just the opening shot in what promises to be a long war. “Online gambling is creating a public health disaster with increasingly addictive products right before our eyes,” Daynard declared in a PHAI statement after filing. “The massive advertising,” he added, “bears an uncanny similarity to what the cigarette companies used to get away with.”

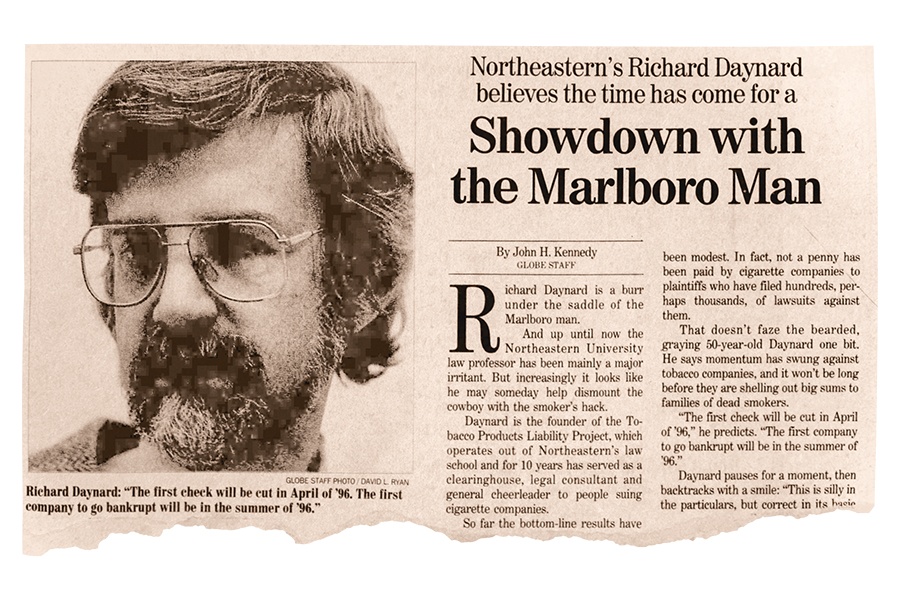

The comparison was intentional. After all, it was Daynard who’d crafted the legal strategy that brought Big Tobacco to its knees—not just by proving cigarettes caused disease but by exposing how the industry deliberately hooked customers through aggressive marketing. In the 1980s, the young law professor assembled a team that used legal discovery procedures to reveal how tobacco companies had deliberately concealed health risks from the public while promoting their products through sophisticated ad campaigns. Their work led to a watershed moment: the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement between 46 state attorneys general and the four largest tobacco companies. The price tag was steep—$206 billion over 25 years—but the real victory came in strict new limits on cigarette advertising. Soon, smoking began to fade from American culture, its once-seductive image extinguished.

Daynard’s battle against Big Tobacco transformed him into an unlikely crusader—a folk hero to public health advocates and a nemesis to anyone tied to the tobacco industry. When Northeastern Law celebrated his 50 years of teaching, they used the headline, with only a hint of irony, “Daynard vs. Goliath.”

Still, it’s easy to wonder if, this time, Daynard has finally placed a losing bet. Unlike tobacco, gambling doesn’t increase the risk of cancer for players or innocent bystanders. And unlike tobacco companies of yore, gaming operators are hardly sitting on their hands, already deploying advanced safeguards, including real-time monitoring and interventions for problem gamblers, as well as self-imposed limits on time and money spent. Meanwhile, betting apps poured more than $100 million in taxes into Massachusetts coffers in the first year of legalized gambling alone. And in a state that won’t even permit happy hour, sports betting offers a rare taste of hard-won excitement.

Yet Daynard, at 81, remains unfazed. His white beard and matted combover frame eyebrows that droop like stalactites over deep-set eyes, but he radiates a determined energy. He’s comfortable being the underdog, learning a new industry from scratch. After all, he knew next to nothing about tobacco before he began that legal fight. As Levant puts it, Daynard might not know a thing about sports or betting, but “he knows a ton about gambling.”

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

The morning I was set to meet Daynard at his office in the Fens, I rolled over, unlocked my phone, and placed a bet on a table-tennis match in Germany—all without leaving my bed. Like many Massachusetts residents, I started wagering after the state became the 33rd to legalize sports betting in early 2023. While Bay Staters’ relationship with gambling predates apps like DraftKings and FanDuel, these platforms have made it a lot easier to get in on the action. No more trips to Vegas, no dealings with bookies, no sketchy offshore websites. Just a few taps on your phone, and you can bet on nearly any game anywhere in the world.

A recent poll from the Siena College Research Institute captures the growing trend: 39 percent of Americans now gamble on sports, with roughly 19 percent holding online-betting accounts. A third of those bettors are men between 18 and 34. I’m one of them.

When I first opened a DraftKings account, I stuck to what I knew: football and basketball. My wagers were small—$5 to $10—and I doubled and tripled my money in short order. Winning was appealing, but what really hooked me was how betting transformed the games. Suddenly, a fourth-quarter blowout became riveting as I watched the losing team inch toward covering the spread. Every play mattered. Every minute counted.

Then, something shifted. I began reaching for the app during lulls in my day, placing bets on anything with odds. Soon, I was gambling on soccer matches in Turkey, Ping-Pong games in Poland—contests I would never have followed in a thousand years had it not been for the apps.

At first, I kept quiet about my own betting with Daynard. I wasn’t losing or winning large amounts—I netted a whole $5 on that table-tennis match—but it still felt awkward to admit to gambling in front of someone trying to regulate it. When I finally confessed, though, Daynard didn’t seem to care. “I don’t think there’s anything bad about doing it,” he said, casually mentioning he’d even tried slots himself.

His reaction addresses a common misconception about Daynard: He’s not a gambling prohibitionist. Daynard doesn’t take issue with bettors—even reckless ones. His target is the companies that he says “hooked them.” What he wants are stronger guardrails around online betting, particularly given the American Psychological Association’s warnings about gambling disorders surging among young people.

Online betting caught Daynard’s attention when Massachusetts first legalized it. While PHAI had dabbled in gambling cases before, filing a lawsuit over unattended lottery machines in supermarkets, and Daynard had studied the psychology of slot machines through books like Addiction by Design, the ubiquity of mobile betting was something else entirely. Suddenly, he felt as though he couldn’t escape it: sports gambling ads wrapped around city trash cans, even his gym trainer had a story about Super Bowl party guests who never looked up from their phones, too busy placing bets to watch the actual game.

That’s when Daynard saw the parallels to tobacco. “We knew there was something going on here,” he said. “And it couldn’t be good.” His suspicions crystallized after meeting Levant, a gambling addiction counselor who’d previously hit rock bottom—stealing almost $2 million from loved ones and associates to feed his addiction before nearly taking his own life. Levant’s harrowing story, combined with his deep knowledge of the industry, convinced Daynard that mobile betting represented nothing less than a looming public health crisis.

Daynard isn’t the only one seeing the warning signs of a growing social concern. At the Massachusetts Council on Gaming and Health, CEO Marlene Warner reports an unprecedented increase in young men calling gambling helplines—a pattern she says emerged only after sports betting went live. Local Gamblers Anonymous meetings are seeing what one leader described to me as “an incredible uptick” in attendance, particularly among young people with betting apps on their phones. The concern has reached such a fever that during March Madness last year, Attorney General Andrea Campbell launched a Youth Sports Betting Safety Coalition, aiming to educate 12-to-20-year-olds about gambling’s risks and regulations.

For Daynard, sports-betting apps are just slot machines in disguise—another way to keep players pulling the digital lever while the house inevitably wins. “It’s not just the notion that, ‘Gee, I might win some money on what’s happening in some ball game,’” he says. “That was the old reason for gambling. What’s addictive about this is the repeated action.”

The allure runs deeper than simply betting on winners and point spreads. Today’s apps allow gamblers to wager on nearly every aspect of a game—from a player’s total points to the coin toss—through “prop bets” that can be placed instantly, before or during a game. Studies show this constant action triggers dopamine releases from the act of betting itself, regardless of whether the user wins or loses.

Massachusetts legislators considered banning these in-game wagers during the long debate over legalization. Daynard wishes they had, seeing these rapid-fire bets as particularly dangerous for vulnerable players. (He’s not alone. At presstime, a new Senate bill was proposed early this year to ban live betting in the state.) And the stakes couldn’t be higher: According to the American Psychiatric Association, studies have shown that half of those with gambling disorders contemplate suicide, and nearly one in five attempts it.

When Daynard initially learned of DraftKings’ bonus offer for first-time users, he knew he’d found his opening. The $1,000 bonus was real enough—but in the fine print was the catch: Players had to deposit $5,000 and place $25,000 in bets within 90 days to collect. The math was simple, the lawsuit alleged. Players would likely lose more chasing the bonus than they’d ever receive.

While research on advertising’s role in gambling addiction remains mixed, a multi-year study from the University of Massachusetts Amherst published in May offers telling insights. Most casual online bettors reported that ads had little influence on their habits. But among those struggling with gambling problems or at risk of addiction, the story changed: They were far more likely to recall ads and acknowledge how marketing drove them to gamble more.

Daynard sees similarities to his tobacco fight. After all, when he first challenged cigarette companies, the odds seemed just as long as they do today with betting apps. “Anybody who knew anything,” he says of those early days, “knew there was no chance.”

Long before he took on Big Tobacco, Daynard had already shown an appetite for risk. While his Harvard Law School classmates followed the conventional path—Wall Street firms, Westchester homes, country club memberships—he walked away from it all. The traditional lawyer’s life felt too confined, too distant from the social impact he craved. Academia, on the other hand, offered something different: an open-ended journey where he could keep learning, eventually earning a master’s in sociology from Columbia and a Ph.D. in urban studies, with a focus on law and social policy, from MIT. More important, it gave him the freedom to search for ways to use his legal expertise for something bigger than himself.

By the early 1980s, Daynard had found his calling in public health, armed with a childhood memory that had never left him. As a boy in New York, he’d belonged to a radio club that met in a smoke-filled room, where he first grasped how cigarettes threatened not just the smokers, but everyone forced to share their air. He decided to join the Massachusetts chapter of the Group Against Smoking Pollution, where he rose to president and set his sights on the tobacco industry. When he later floated the idea of taking on Big Tobacco to his consumer protection students, their response, he said, was simple: “Sue the bastards.” Their words lit a fire that burned for decades.

Long before he took on Big Tobacco, Daynard had already shown an appetite for risk.

Teaming up with a psychiatrist friend, Daynard launched the Tobacco Products Liability Project, hosting meetings in his Commonwealth Avenue living room. From there, he orchestrated a masterful campaign: advising attorneys from Mississippi to Massachusetts, holding press conferences to skewer cigarette makers, and becoming both a constant media presence and the industry’s bogeyman—all without ever making an argument in court.

In part, Daynard’s skill lay in his ability to strategize and collaborate. While lawyers had been fighting—and losing to—tobacco companies in isolated one-off cases, Daynard united them, creating a network to share medical evidence and legal strategies. “He didn’t want to do anything that was just sort of nibbling at the edges,” says Carol, his wife of 50 years. “He used to say, ‘I want to do something wholesale, not retail.’”

More than three decades ago, Gottlieb was in Daynard’s toxic torts class, watching his professor sit cross-legged on a table, guiding discussions before rushing off to tobacco litigation press conferences. “He was the only professor I had who looked at using the law in a completely different way as a lawyer than I had ever contemplated, which was to improve the health of large numbers of people—population health,” Gottlieb says. “I never really had thought that an attorney could do that.”

Still, many lawyers thought Daynard was wasting away his career. By the late 1980s, tobacco companies had brushed off 321 liability cases without a single loss since 1954, as the New York Times reported. Even those who shared Daynard’s public health concerns saw his cause as hopeless. Allan Brandt—who would later write the Pulitzer finalist The Cigarette Century—warned him that American culture’s devotion to personal responsibility would doom any attempt to hold cigarette makers accountable. Yet challenging conventional wisdom no longer unsettled Daynard. “At some point,” he told me, his New York accent still audible beneath the rasp of a cold, “I sat around and said, ‘Wait a second, there’s a name for people who believe things that nobody else believes: Am I psychotic?’”

Daynard refused to fold. Instead, he turned the fight against Big Tobacco into a war of attrition—one that would ultimately reshape American public health. Scientists had been linking smoking to lung cancer since the 1950s, and by 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General had officially declared it a health risk. Yet the tobacco industry had never admitted to knowing its products caused cancer. Then, in 1987, Daynard uncovered a damaging document proving that R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company had acknowledged cigarettes’ links to cancer and heart disease while publicly denying the science to their consumers.

The following year, a jury awarded $400,000 to the family of a lung cancer victim who’d been a lifelong smoker—the first time Big Tobacco had ever been ordered to pay a dime in court. Though that ruling would later be overturned, and countless courtroom defeats would follow, each trial offered fresh opportunities. Through discovery, more damning documents emerged, and public opinion began to shift. “You could lose cases, but win,” says Brandt, now a Harvard professor of medicine and science history and a board member of the PHAI.

Eventually, states had seen enough. With mounting Medicaid costs from smoking-related illnesses, they started filing—and winning—their own lawsuits. It all culminated in 1998, when the largest cigarette makers signed the Master Settlement Agreement. The deal was unprecedented: Tobacco companies would pay states billions annually, in perpetuity, in exchange for protection from state and local government lawsuits. The agreement barred youth-targeted advertising and limited sponsorships. But crucially for Daynard, it left the door open for individual and class-action lawsuits.

The Master Settlement hardly put an end to Daynard’s fight against tobacco. He and his colleagues kept filing lawsuits, knowing the industry hadn’t truly surrendered. “It wasn’t as if the industry had thrown in the towel. It wasn’t as if they weren’t still trying to figure out how to get people hooked and keep them hooked,” he says. “So we were still encouraging lawsuits against them and hoping to at least keep the pressure up so that they didn’t come up with any new tricks to get kids hooked.”

Over time, the tobacco lawsuits drew criticism for mainly enriching attorneys, who collected massive contingency fees. Lawyers from the states involved in the Master Settlement Agreement raked in billions. While Daynard says he approaches gambling litigation with principles in mind, others might see it as their next big payday—though it’s too early to tell, since this legal battle is just beginning.

The impact of the tobacco litigation was seismic. Cigarette makers, forced to pay sky-high settlements, hiked their prices. By 2005, sales had plunged to a 55-year low, and by 2019, consumption had been cut in half, with youth smoking plummeting from its 1997 peak of 36 percent to just 6 percent. Much of this transformation traced back to a scrappy Northeastern lawyer who never stopped pressing, even after the settlement. “He turned the tide for public health,” Brandt says.

Even as the tobacco battle raged on, Daynard began searching for his next cause. In the early 2000s, he thought he’d found it in America’s obesity epidemic, taking aim at junk food and soda manufacturers. But when PHAI’s lawsuit against Coca-Cola fizzled, he shifted his energy to teaching, finding deeper satisfaction in mentoring the next generation of public health lawyers. Still, he never stopped scanning the horizon for that one final fight, that last public health battle to wage before hanging up his yellow legal pad. It would take two decades before he found it.

In online betting, Daynard discovered a public health crisis he could tackle with the same legal playbook. “We got involved in this because of analogies with tobacco,” he says. Just as cigarette makers had done, he argues, gaming companies have engineered an addictive product while blaming consumers for its potentially devastating effects. Only this time, they’re wielding sophisticated technology instead of nicotine.

In the end, taking on the betting industry could prove to be Daynard’s riskiest gamble ever. After all, unlike smoking cigarettes, a sports-betting app doesn’t cause cancer, heart disease, or have an impact on one’s physical health. And between state officials counting their tax revenue windfalls to happy bettors to the betting operators themselves, it’s hard not to wonder whether the veteran lawyer has finally picked a fight he cannot win.

Photo by Tony Luong

Under the bright lights of Encore Boston Harbor, House Speaker Ron Mariano clutched a betting slip in his hand. Flanked by Boston sports legends Johnny Damon, Ty Law, and Cedric Maxwell in January 2023, he was savoring the moment: After years of legislative wrangling, sports gambling was now legal in Massachusetts.

Mariano had won over legislators with a straightforward pitch: Why leave in the shadows what could be regulated and taxed? The public needed little convincing—most voters in Massachusetts already backed legalization. And in a state notorious for its strict liquor laws and early last calls at bars, residents were eager for a new form of entertainment, especially one that tapped into their sports obsession. “I think you are looking at a potential gold mine,” Mariano told reporters after the ceremony.

Mariano’s prediction hit the jackpot—but not exactly the way the casino-floor event suggested. In the first year alone, Massachusetts hauled in $108 million in sports-betting tax revenue, dwarfing projections of $30 million to $60 million. But the real action wasn’t at gaming tables; it was in people’s pockets. When mobile betting launched in March 2023, it quickly claimed 97 percent of all wagers. Since then, betting apps have blanketed the airwaves with ads, enlisting local sports heroes, including Rob Gronkowski and Zdeno Chara, to pitch an endless stream of entertainment that generates headlines, engagement, and—most of all—big bucks for the betting operators.

From its humble beginnings in a Watertown spare bedroom, DraftKings has emerged as a gaming industry powerhouse, projecting $5 billion in revenue for fiscal year 2024. While proponents argue that companies like DraftKings are making gambling safer by bringing it into the sunlight of a regulated market, there are still concerns about the financial and psychological dangers. To combat the issue, DraftKings says it’s monitoring user activity to spot problem gamblers before they spiral, and in April 2024, the company underscored its commitment by naming its first chief responsible gaming officer, Lori Kalani.

With experience in consumer protection policy and working with regulators, Kalani also brings a hard-won and unique perspective to the role. Growing up in Las Vegas, she watched both of her parents battle gambling addiction. “They were not able to play responsibly, and as a result, I ended up out on the street,” she told me. Yet Kalani also saw gaming’s social appeal—how visitors flocked to Sin City for a fun weekend. She views online sports betting through a similar lens. “This is entertainment for adults,” she said. “I see this as somebody either wanting to go to a live sporting event and spend $1,000 for the playoff ticket, or maybe they would rather spend their money socializing with their friends, competing with their friends—having skin in the game.”

Kalani is proud of DraftKings’ commitment to responsible gaming, including advanced technology. The company has built an arsenal of protective measures: deposit limits, wager caps, and time restrictions that players can set themselves. Users can even opt for “self-exclusion,” blocking their own access to the platform for up to five years. Behind the scenes, artificial intelligence scans player communications for red flags, while a dedicated team reviews player activity and transactional data, and reaches out to at-risk users. Their interventions range from sharing educational resources to requesting proof of financial stability or, when necessary, suspending accounts. The company also provides its customers with direct access to mental health services.

Gaming industry advocates argue their safeguards set them apart from underground or black-market operators. “The neighborhood bookie does not care if you’re chasing losses,” says Joe Maloney, the senior vice president of strategic communications for the American Gaming Association. “The offshore website is not going to serve you up a message about, ‘Hey, maybe it’s time to take a break.’”

Gaming advocates also bristle at Daynard’s tobacco parallel. “There’s no such thing as safe and responsible use of tobacco,” Maloney points out, warning that lawsuits like Daynard’s could backfire. “The vast majority of individuals who choose to place bets on sports, either in person or online, do so responsibly,” Maloney says. “So the idea of draconian advertising restrictions or outright bans is simply going to negate all of the efforts we have made as a country to migrate bettors out of the illegal market into the legal market.”

In response to PHAI’s lawsuit, DraftKings filed a motion to dismiss the claims, arguing that PHAI had “cherry-picked portions of the Promotion’s advertising and sign-up process,” conveniently ignoring the pages of clearly displayed terms that users had to view during sign up. Though the motion was denied, DraftKings attorney Richard Patch remains confident. “Do you think it’s really true that a person is so naive as to think, ‘I put down a $5 deposit and get $1,000 in U.S. cash and walk away with it?’” he says. “I mean, it’s just not realistic. People have to be fair, and some common sense has to prevail in these situations. I think common sense will prevail here.”

Photo by Tony Luong

Daynard isn’t limiting the fight to the courtroom. This past September, Levant and Gottlieb stood on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to help introduce the SAFE Bet Act, the first bill targeting the public health effects of online sports gambling. The legislation would ban sportsbook advertising during games, restrict certain promotional bets that could “induce gambling,” and cap daily deposits. It would also prohibit the use of artificial intelligence to track user behavior—which Daynard believes companies deploy not to identify problem gamblers but to target their most profitable customers. He’s confident future legal discovery will prove him right. (For their part, DraftKings says Daynard is off base. “DraftKings is committed to using technology responsibly to provide an entertaining gaming environment that players can enjoy responsibly. Any suggestion or claim to the contrary is an outright misrepresentation,” the company said in an email. )

At 81, when many of his peers have long since retired, Daynard keeps working. He’s a grinder. And he doesn’t take no for an answer, Brandt told me. Until a doctor tells him he has to stop working, he says he’ll still be at it.

When I spoke to Daynard in December, he was optimistic; it seemed the eventual outcome of the suit against DraftKings wasn’t weighing heavily on him. In fact, PHAI is already preparing another case for 2025—DraftKings is just the opening salvo. “The point,” as he told me earlier, “is to try to dissuade them and their competitors from doing this kind of deceptive marketing, designed to bring people in who might not otherwise be betting.”

Make no mistake: Playing the long game carries its own risks. While more cases can unearth damaging evidence and gain media exposure, mounting losses can bankrupt law firms and discourage others from going to court. “It’s a scary proposition,” Daynard admits, “until public attitude and understanding changes.”

Still, Daynard has faced this skepticism before. He’s confident that, as with tobacco, people will eventually catch up to his thinking and recognize gambling as a public health crisis. “I bet,” he says with a knowing look, “we’re going to see a revolution.”