Of all the deeply upsetting details in Tom Huck's relentlessly unsettling oeuvre, the dog dick has to take the top spot.

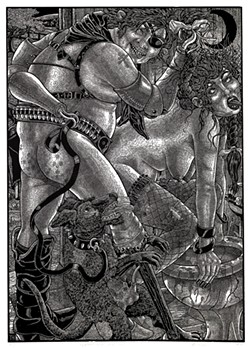

The distressing bit of canine anatomy appears in what Huck himself has acknowledged may be his "most heinous print," "Anatomy of a Crack Shack," which was released in 2005 as part of his Bloody Bucket series. The 50-inch by 32-inch work depicts an act of physical congress between a woman in fishnets bent over a befouled outhouse toilet and a World War II veteran with hooks for hands, a peg leg and an eyepatch. Both their faces are twisted into toothy displays of carnal delight, such that it's almost believable that neither character registers that a pooch with a spiked collar and a horrifying dog boner is getting in on the action as well.

It's a truly harrowing set of genitals, replete with the retracting-lipstick action for which man's best friend is well known, as well as a disproportionately prodigious length.

It's also the dog dick that almost wasn't.

"While I was drawing that dog wiener on there, I was telling myself, 'Huck, don't put that in there. Don't do it. Don't do it, Huck,'" he recounts. "I did it — and I felt better."

It's a fascinating insight into the twisted process of the Missouri-based master printmaker, who is widely and correctly regarded as one of the best there is at what he does. Known for his oft-profane large-scale satirical prints, created through a painstaking process that dates back to medieval times, Huck wields a talent so undeniable that his work can be found in private and public collections across the world, with pieces included in the Whitney Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, the Saint Louis Art Museum and countless others.

The behind-the-scenes tale of that dastardly dog's disturbing dick comes via a new hardback retrospective of Huck's work entitled Tom Huck: The Devil Is in the Details, the newest release by boutique St. Louis publishing house Fine Print Small Press, operated by self-described "serial entrepreneurs" Chris Ryan and Jim Harper. Clocking in at more than 300 pages and authored by writer and archivist Greg Kessler, the book offers a granular examination of Huck's prints from 1995 through 2020, with stories and quotes from the man himself that offer something of a backstage pass into the inner workings of a madman's mind. Fitting for an artist of Huck's esteem, the book was officially released into the world in late October with a signing and print demo at no less than the Met in New York.

The weighty 12 by 12 inch tome's origins can be traced back to just before the pandemic, when Harper and Ryan met with Huck about creating a comprehensive collection of his works. It wasn't the first time he'd been approached in this way — but right away, he could tell the two had a vision.

"There have been a lot of other attempts by people — failed, usually, either for lack of prolonged interest or finances and all that. Books never got done," Huck tells the RFT. "But I got the immediate impression that they were in it for the long haul and they wanted to do it right. ... They convinced me. It took a long time, but they got it done, and it's a fantastic representation of [my work].

"Some of the stuff in there I don't even remember doing," he adds. "It was crazy."

Ryan and Harper had worked together previously on commercial projects through their individual businesses — Ryan's Once Films company in Midtown St. Louis and Harper's design firm Harper's Bizarre. Through that work, they hit it off and became friends, ultimately deciding to launch Fine Print Small Press as a way to bring into the world bespoke physical artifacts that they themselves simply wanted to own, including books, vinyl records and the like.

A hardcover collection of Huck's work was at the top of the list.

"Very much the endeavor for us to even work on these kinds of cool side projects is, as we describe it, to put things out in the world that we wish existed," Ryan tells the RFT. "We knew we wished a book of Tom's work existed. I know I did, and when I talked to Jim we were like, 'Yeah, that should exist. Why does it not exist?' And if we're gonna do it, we're gonna do it big."

"We had been talking about doing some projects together for a long time," Harper says. "Chris was like, 'We need a book on Tom Huck. ... I love Tom's work; you have to go all over the place to see it. Most of it sells out; it's hard to see, and I want to talk to him about it.' He had met Tom before, I had not."

In that first meeting, everything just clicked. Not only did the vision they had for the project pique Huck's interest, they also had some shared experiences over which they quickly bonded.

"Both of our first concerts were KISS with our moms in 1978," Harper says with a chuckle. "There were all kinds of ways we hit it off."

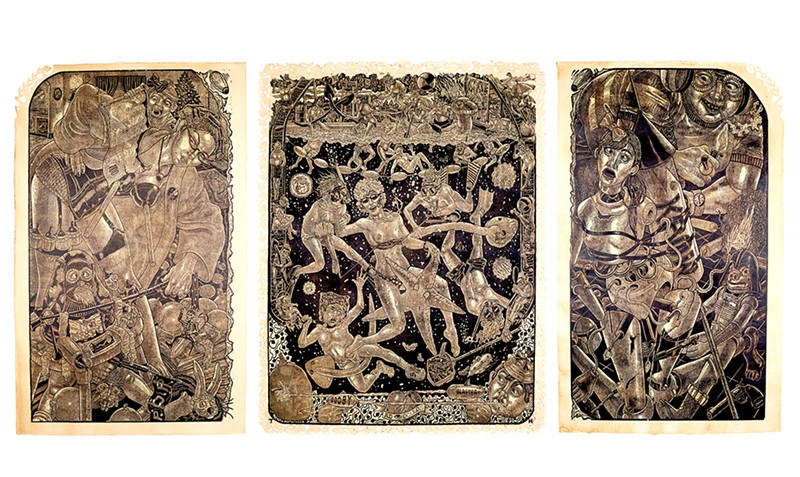

With the green light from Huck, Ryan set out to accomplish the difficult task of photographing all of Huck's pieces since 1995 — no small feat, especially when one considers Ryan's own point that Huck's work is scattered across various collections around the world. Further complicating things was the sheer scale of some of the prints. His 2017 triptych Electric Baloneyland, for example, is widely credited as the largest chiaroscuro woodcut in the world, measuring 86 by 108 inches. In order to properly shoot something of that size, Ryan and Harper had to get creative.

"Chris, at one point, built a contraption, a structure with the camera hanging in a bird's eye, so we could lay the large ones down in the studio," Harper explains. "Because there was literally no other way."

But right as things were really in full swing, the COVID-19 pandemic came along and ground the world to a halt. In response, Ryan and Harper shelved some of their other planned projects and poured all of their focus into the book. They brought in longtime St. Louis punk scene archivist and writer Greg Kessler to handle the text portions of the collection; Kessler then participated in a series of freewheeling Zoom sessions, emails and, eventually, in-person interviews with the three, as well as Huck's longtime friend and collaborator Levi Banker, from which he was able draw out the stories and details behind some 25 years' worth of work. Kessler took his inspiration for the form the text would take from the liner notes of the 1984 greatest hits album No Remorse by Motorhead —Huck's favorite band, and one he'd even had the pleasure of working with professionally over the course of his career.

Rather than appearing as large blocks of text covering multiple pages, most of the introductions of the various works and the stories behind their creation are presented in smaller chunks interspersed between Ryan's photography of Huck's work, which through Harper's design prowess is presented in a manner that allows the reader to focus on the incredible level of exacting detail in the art itself. All the different pieces are shown in their full form, but then Ryan would also zoom in on specific details he particularly enjoyed, which allows the pieces to be viewed in a new way while also subtly encouraging readers to seek out their own favorite bits.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the book is the inclusion of two of Huck's sketchbooks, which show early versions of Huck's best-known work, as well as ideas that haven't yet made their way to the wood just yet.

"This might have been my favorite part of the whole thing," Ryan says. "You know, I'm a behind-the-scenes, in-process guy, right? I love to peek behind the curtain. For me to get into his journals and photograph all those, and for us to flip through them and find, like, weird artifacts from you know, 15 to 20 years ago or whatever — just a really cool experience."

Three of the illustrations from those sketchbooks appear to be rough, early versions of "Anatomy of a Crack Shack." Sure enough, no dog boner appears in any of them.

Nestled at the foot of the Ozark Mountains in a rural community about an hour's drive south of St. Louis — or three dead roadside deers' worth, depending on your preferred unit of measurement — sits Huck's Park Hills headquarters, Spiderhole Studio. There, seated in a small round chair in early November, Huck has a different set of dicks on his mind.

It's the day before the 2022 midterms, and the nation is on edge. The Democrats have crowed on and on for months that it's the most important election of our lifetimes, that fascism is at our doorstep, that democracy itself is on the ballot. Republicans, meanwhile, have gone all-in on the culture wars, targeting drag queens and trans rights and critical race theory in what they are sure will be a winning campaign of hate, a red wave to sweep them into power.

Befitting a satirist, Huck has a more nuanced view of the matter.

"Tomstradamus is making a prediction that maybe it's 50-50," he says between bites of a cheeseburger. "I don't think it's going to be as bad as the liberals think it's going to be, and I don't think it's going to be as good as the Republicans think it's going to be. I think it's going to be 50-50, and we're still going to keep the Senate. ... But the House? That's a murderer's row of whack jobs over there. Anything goes over there."

For the most part, Huck would be proven correct. In a climate of endless takes from countless armchair political analysts, the guy best-known for making deranged art out of hillbilly fables and canine genitals has somehow delivered the savviest assessment of the current political landscape. The Nate Silvers of the world could learn a thing or two.

Actually, though, it's not that surprising. Huck's work has increasingly trended toward broader social commentary over the course of his career, and like any good satirist, he's proven himself a keen observer. Whereas he approached his early pieces as a sort of revenge against his surroundings in rural Potosi, Missouri, savagely targeting the cast of characters he grew up with, he's since pulled the lens back and focused more on American society as a whole.

An argument could easily be made that the culture at large has simply finally caught up to Hück's view of it.

"It is kind of hard making the kind of work that I make, looking at this stuff happen," he says. "Like a January 6 — that's some shit I would make up! A dude wakes up in the morning and decides to dress up like Yoda and go overthrow the fucking government on the date of certification day. That's the kind of shit that I'd come up with over about six fucking years. 'Oh, I'm gonna make the next body of work about this.' It's got built-in surrealism, it's metaphoric, it's allegorical and hillbillies are involved. That's the whole life of my work! And it played itself out, so how the fuck do you top that, what's really going on? I mean, it threw me a little bit."

He pauses a moment before continuing. "You gotta be a certain breed of individual to wake up in the morning and say, 'Honey, today I'm gonna overthrow the government. Where's my loincloth?'"

Huck's latest work, A Monkey Mountain Khronikle, is his attempt to at least match the absurdity of the times we're living in. A collaboration between Huck's Evil Prints and Peacock Visual Arts out of Aberdeen, Scotland, the front-and-center panel of the 48 by 96 inch double-sided triptych introduces the viewer to Lord Aporkalyptus, a creature with a skeletal animal face, clad in religious vestments adorned with hot dogs and burgers, holding a banner that reads "ALL YOU CAN EAT." Below him, deranged angel-like figures force-feed food products to several onlookers whose faces indicate their willingness to consume.

On the reverse side, also in the center panel, we meet Mr. Wiener McPicklehead, a ghastly clown-beast with a burger for a head that is topped with more hot dogs, as well as onion rings, pickles and several bugs crawling on its outer bun. Flanking him on each side are his Kat Bats, which are exactly what you're picturing, and the Gooey Guardian Girlz, horned women with snake bodies being fed slices of pizza while McPicklehead tucks into the largest banana split ever conceived, complete with human bodies among its toppings.

The other scenes depicted on the triptych's panels are similarly food-focused, and similarly unsettling, with Nazi-esque and Klan-esque figures making appearances as well. On the predella across the bottom are the words, "WE EAT. WE SLEEP. WE HATE. REPEAT."

"It's all about gluttony," Huck says. "American gluttony in all of its forms. In politics, religion, conspiracy theories. All of it rolled together into one. Pop culture, bad food, all of it. It's all about how MAGA figured out how to market to that 30 percent of people who are sports fans. Just give it a good brand and a uniform, and we'll sell it to you like a sugar-laced Big Mac. That's what it is. It's sloganeering and logo-ing that got people."

A Monkey Mountain Khronikle took Huck five years to complete. Huck's process sees him first sketch ideas for a piece before drawing it on a slab of birch plywood; from there he uses a gouge tool to carve the image into the wood, making tiny motions in a painstakingly detail-oriented process that would drive most to madness. Since the end goal is to use the block to transfer ink to paper, Huck must carve the mirror image of what he's envisioned in his mind, adding an extra layer of complication. Work on this latest project started in 2017 in Scotland, where Huck labored for 12 hours at a time to complete the first block. When COVID-19 came, Huck hunkered down in his Park Hills studio and finished the piece, which made its preview at New York's Print Week in late October before being debuted online at lordaporkalyptus.com the week of Thanksgiving (naturally).

It's among Huck's sharpest pieces of satire to date, an unyielding condemnation of modern society and consumerism in the Trump era. "A Monkey Mountain Khronikle presents real-world horrors wrought by our own hands and catalogs the innumerable ways in which we have fallen short in our mission to give a damn about one another," reads its description on the website in part.

"I think that's where we're at," Huck says of the piece. "We've been fed a bunch of stuff. Willingly. And we're seeing the fallout. ... They got us where they want us, man, as consumers on all levels. And it freaks me out."

Walking into the Locust event space Work & Leisure on December 8, the first thing you see is a bunch of dicks. In a new twist on an old theme, these particular penises are made of hot dogs, with little pretzel balls for testicles. Dick dogs, if you will.

Those come courtesy of Steve's Hot Dogs, which made them as a special for Huck's St. Louis book release and signing, which is also A Monkey Mountain Khronikle's local debut. A sign accompanying the dogs reads "The Buffet of Lord Aporkalyptus," which is fairly unsettling when one is familiar with the work that served as the food's inspiration.

Further inside, a crowd gathers around the completed triptych as Huck sits in the corner with a marker in hand. Harper and Ryan are here as well, mingling with guests and excitedly discussing the newly published book. Black Sabbath plays over the stereo, and a mini-documentary depicting Huck at work is soundlessly projected on the wall as attendees chat among themselves about the art on display.

Sherita and Allan Gober used to be Huck's neighbors, but according to Allan they really got "indoctrinated" (his word) after seeing his work at Saint Louis University. Describing the new piece as "one hot, fast-food mess," the two are impressed with the incredible level of detail in all of Huck's output.

"A lot of times, when you look at it a second time, it's like watching a movie for the second time," Allan notes. "You notice things you didn't notice before, like, 'Oh, there's something in that coffee cup I didn't notice,' or you see faces, like, 'There's people on that bus there.' And, you know, there's a lot going on there. There's things happening behind the scenes. For me, it's just the intricacy that is so impressive."

Tree Sanchez was first exposed to Huck's art when she was 14 years old. Her uncle took her to the Saint Louis Art Museum, where she saw his 2009 piece The Transformation of Brandy Baghead. She was blown away, she says.

"That was the first experience I had where it was like, 'Wow, I didn't know if this type of art could be made before,'" she says. "I was always excited to see more Tom Huck stuff the older I got."

Joe and Janet Huck have arguably known Huck longer than anyone, being his parents and all. They too were on hand for the release of the book. They say that Huck's interest in art and illustration was apparent from a young age. He was constantly drawing, they recall.

"In the early years it was all action figures," Joe says. "Like Superman, comic book characters and things like that."

"But he never would draw women," Janet says. "So his art teacher in junior high ... she said, 'I'm tired of seeing you draw just men. I'm gonna teach you how to draw a woman.' Well, she did. The rest is history on that."

Janet is actually afforded a unique perspective on this particular matter, having been depicted in one of Huck's pieces. In the first panel of his 2014 work The Tommy Peeperz, Janet is shown in bondage gear with curlers in her hair and plungers stuck to her breasts, catching a young Huck in the act of looking at his dad's porn stash. It's probably not what she or Joe envisioned when they first bought Huck art supplies as a child, but nevertheless they say they are extremely proud of their son and how far he's come on his artistic journey.

"I keep up with him and try to keep him on the straight and narrow," Joe adds. "But it ain't worked yet."

Seated in the back of the room, Huck takes a copy of the new book from an attendee and writes "DON'T FUCK THIS UP" in all caps with a gold marker. "I don't know what it means. Just kind of a catch-all," he says with a laugh while signing his name.

Before he hands it back, he scribbles a few doodles on the page and asks for requests.

"I got you a cross, a spade and a skull," he says. "Anything else?"

The owner of the book says it looks good. But Huck thinks for a second before asking a question that's evidently a constant in his mind.

"How about a dick?"

Coming soon: Riverfront Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting St. Louis stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter