Some Australian rural communities suffer worse internet access than some “poor villages” in Africa, which is impeding decarbonisation and efficient production in regional Australia, the economist Ross Garnaut has said.

“Connectivity in the modern world is very important to efficient decarbonisation, but also to efficient production,” he said.

“It’s a tragedy that some rural communities in Australia have such poor access to the internet and potentially that it’s so much poorer than some poor villages I know in Africa.”

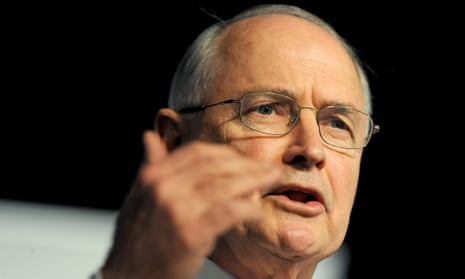

Garnaut is a professor of economics, a former Hawke government adviser and the author of a number of climate change policy reviews as well as the review of the wool industry. He has been the chairman of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research and a director and chairman of the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute, the world’s leading institution for research on rural development.

In a book published this month, The Superpower Transformation, he argues that connectivity is one of the hurdles standing in the way of low and zero-emissions economic growth that would disproportionately favour rural Australia if the regions seize the opportunities.

Weed-spraying technology to reduce chemicals, water monitoring, soil-moisture probes and robotic devices all need connectivity to take advantage of technological gains.

Since federation, economic growth had disproportionately favoured half a dozen big cities. However, that pattern could be reversed given the potential in renewable energy production, urea manufacturing, carbon sequestration and decentralised energy supply.

In a wide-ranging interview about the future of rural Australia, Garnaut said there were positive and negative factors pushing the regions towards the new economy.

He said labour shortages would continue to force all sectors, particularly agriculture, to “economise” the workforce. But he indirectly criticised Coalition plans for a special agricultural worker visa from south-east Asia.

“Australians invented mechanical shearing because labour was scarce,” Garnaut said. “We were faster in large-scale mechanical milking of cows than anyone else because labour was scarce.

“We were in the forefront of mechanical harvesting and sowing and the stump jump plough. And that’s the future of farming in Australia, improving technology with labour efficiency.

“And anyone who thinks that the future of Australian farming was to get cheap labour from the paddy fields of south-east Asia is dreaming as vividly as WC Wentworth when he put the same proposal to the New South Wales legislative council in 1850.”

The farm sector has a huge amount at stake in the face of global warming. Garnaut said that from late 2025 the European Union would place extra tariffs on goods coming from countries it considered were not pulling their weight on climate change, particularly countries that do not have a carbon price.

He predicted businesses that could show a zero-emissions supply chain would overcome the penalty for not having a carbon price in their country.

“Unless we’re really pulling our weight, then they’ll find ways of not only putting a penalty on us for not having a carbon price but adding a bit on and making it harder because the European Union loves some protectionism.”

after newsletter promotion

Garnaut also sees commercial room for a dozen or so small-scale urea plants in country towns across Australia, each providing several hundred local jobs, to lower the cost of urea and increase the supply. Urea is used as an agricultural fertiliser and also as an additive, known as AdBlue, to reduce emissions in diesel engines.

This year, farmers and truck companies have faced high urea prices as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, uncertainty of Middle East supplies and Chinese restrictions on the export of fertiliser.

Australia currently uses 2m tonnes of urea while the world uses 180m tonnes. Australia’s single producer, Incitec Pivot, supplies 10% of the country’s needs and it has announced it will shut in late 2022.

As communities become more interested in generating their own renewable energy through decentralised microgrids, places such as Yackandandah have raised questions about the cost of infrastructure.

Garnaut said removing the regulatory burdens on community microgrids would be a start.

“It’s reasonable for rural communities to expect similar levels of subsidy to anything that’s happening to large-scale distribution of power. But within that framework, it will often be cheaper to provide power in a decentralised way in rural Australia than in the old centralised way.”

In spite of the climate wars that have dogged carbon policy in the past decade, Garnaut remains optimistic about the opportunities for generating carbon value from the land.

“We won’t be converting higher value agricultural cropping, or the best pasture land into carbon sinks – that will make no sense whatsoever. The economics won’t favour that. But there will be opportunities for poorer land, of which every property has got a bit, but also for restorative farming for increasing carbon in soils.”