The tale of Gretchen McRae ends with a cliffhanger.

It might be what first captures your attention about the longtime Colorado Springs resident, but there’s much more to be recognized and celebrated with the civil rights activist and artist who, in 1943, became the first Black woman to run for City Council.

“The details of Gretchen McRae’s life are sketchy, because there are few people alive who knew her well, and because her public life was ill-reported by a press that was as slow as its society to recognize worth beneath the surface. But a picture does begin to form as those who did meet her, however casually, cannot avoid the word ‘brilliant.’ Not quite so obvious, but still discernible, is that she had guts to match the brains,” wrote Gazette Telegraph reporter Ed Ashby in 1978 after McRae’s death.

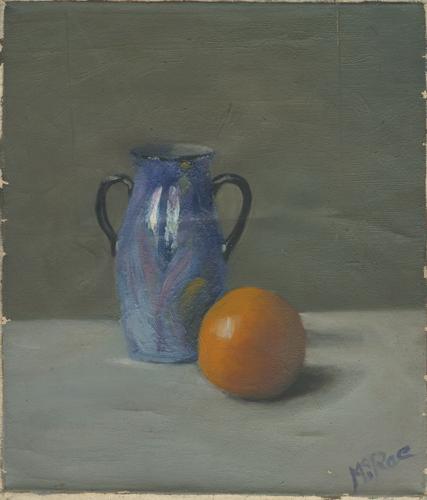

Caroline Blackburn, now a New Mexico artist, became particularly interested in McRae in 2006-2007, as she volunteered at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. She organized and cataloged the Areba Jackson Collection, which contains artwork, materials, handwritten notes, typewritten letters and more from McRae’s life. Blackburn went on to write a paper about the activist that was included in “Extraordinary Women of the Rocky Mountain West,” a book published by Pikes Peak Library District.

She describes McRae as driven, intelligent and unafraid to speak her mind, even when those around her might have preferred she stayed more quiet. But she wanted the best for her community.“She wanted to achieve rights for Blacks by focusing on equality,” Blackburn says.

“She was pretty adamant that the conversation surrounding segregation and desegregation should be dropped. She felt like what the government and community needed to talk about was how to make citizens equal.”

When the city wanted to put in a recreation center south of downtown for the Black community, she was adamant it wasn’t a good idea, even though it might have appeared to be on the surface: “It needed to be just a community center, not a Black one because that’s segregation,” Blackburn says.

McRae was about 5 when her family moved to town in 1903, settling into a home at 822 S. Weber St., in the new, mostly Black neighborhood south of downtown. They also bought a home at 805 S. Weber St. Both dwellings are now gone in the wake of redevelopment.

She graduated in 1917 from Colorado Springs High School, now Palmer High School, and in 1918 made a bold leap by moving to Washington, D.C., where she worked as a clerk and stenographer in the U.S. Department of Interior.

It was there McRae began to fold herself into the civil rights movement for Black Americans, which included becoming a delegate at an NAACP conference and advocating for the desegregation of her workplace. She also continued to develop her artistic streak by taking classes at Howard University.

When her bid for desegregation at work was denied in 1929, she quit in protest and moved to New York City, where she briefly attended Cooper Union Women’s Art School. Typewritten letters in 1931 to a school administrator indicate she felt racial discrimination after expressing displeasure about racial slurs included in the school’s “Pioneer” publication.

“This is persistent propaganda to create disrespect for a certain group of people, and I believe it is contrary to the wishes of the founder and the principles upon which the school is built,” she wrote.

In 1932, McRae returned to Washington, where she put out the pamphlet, “Have you Depressionitis?,” and landed a meeting with Secretary Harold Ickes to ask for desegregation in the Interior Department.

“She had a strong interest in art,” says Blackburn, “but her feelings that she needed to do something more for the civil rights movement meant her energy needed to be focused on writing essays. Writing letters to government officials and letters representing the NAACP became more important than doing art.”

Her Washington years ended in 1937, when her grandmother died, and she moved back to Colorado Springs. Blackburn remains perplexed that a young Black woman who had been courageous enough to leave town and become actively involved in the civil rights movement wasn’t written about in the newspaper or invited to speak at the college.

“She dissolves into history. You don’t really hear about her. In Colorado Springs, people don’t really understand what she’d done, and if they did it wasn’t talked about in big circles,” she says. “I could speculate it was because she was Black. When she was a kid, the Ku Klux Klan stronghold was Denver and the Springs had a huge following of white supremacists. I’d wager there was still a lot of that seeping into the ‘40s and ‘50s. Maybe it was that or she just became a recluse.”

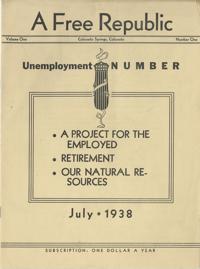

McRae lived in one of the family’s homes on Weber Street and began publishing her essays on equality in her magazine “A Free Republic.” It ran for three years and included poetry, fiction, cartoons and recipes from a mix of contributors.

“The depression is caused not by a lack of resources or anything tangible, but by such intangible qualities as these which can wreck a nation: acquisitiveness, incomprehension, selfishness, stubbornness, or greed, which is a combination of the first four,” she told her readers in one issue.

McRae’s story ends with a surprising and gruesome twist. In 1978, after a postal worker noticed that neither she nor her sister Almena had picked up their mail for a few days, Gretchen’s body was found in the house. She’d died of a heart attack a few days earlier. Almena’s body also was discovered. She’d died four years earlier of natural causes, but Gretchen had kept her in the house, wrapped and mummified in paper towels and propped on a chair.

“That story seems like what Colorado Springs remembered her for,” Blackburn says. “That’s really unfair because the most interesting parts of her life were when she was a young woman getting involved in the civil rights movement. It was really hard to do that in the early 1920s and 30s, and for a Black woman to be speaking up was even more brave.”

Blackburn can only speculate as to why Gretchen didn’t report her sister’s death.

“If I were her, I would have been very frustrated at that point,” she says. “If you felt like you weren’t listened to and couldn’t make a living doing what you really wanted to. Her sister was the only person who probably understood that. Gretchen didn’t want to let go and be on her own.”

Contact the writer: 636-0270

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices