Poland’s nationalists have won their latest battle to defend the country’s wartime reputation. On Tuesday, the Warsaw district court ordered two leading historians to apologise to a woman for defaming a relative in their book about the Holocaust. The landmark ruling has serious implications for academic freedom and the future of Holocaust research, with historians around the world condemning the judgment.

“These are not matters to be adjudicated by courts, this is a point that can be discussed by scholars or interested readers in the exchange of opinions. In that sense, it’s really scandalous,” says Jan Tomasz Gross, whose seminal book Neighbours was a watershed in Poland’s public discussion of the Holocaust more than 20 years ago. “It’s part of a broad effort to stifle any inquiry and particularly the complicity of the local population in the persecution of Jews during that time.”

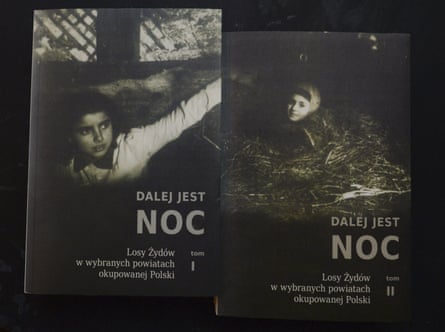

In Night Without End, a forensic two-volume history that totals nearly 1,700 pages, professors Barbara Engelking and Jan Grabowski focus on the fate of Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland after the Nazis began liquidating the ghettoes in 1942. The book includes a brief passage based on the testimony of a survivor, Estera Siemiatycka, who accused Edward Malinowski, a village elder in Malinowo, north-east Poland, of collaborating with the Nazis and denouncing a group of Jews in hiding.

Malinowski’s niece, 81-year-old Filomena Leszczyńska, sued the historians. The Polish League Against Defamation financed the case, claiming in a lengthy statement that the historians had damaged “the reputation not only of Edward Malinowski, but also other Poles, or even Poland” and accused them of “careless use of historical sources”. The League is a handmaiden to Poland’s ruling Law and Justice Party’s political agenda to burnish the country’s wartime image. With the mission “to initiate and support actions aimed at correcting false information on Poland’s history”, the League has pursued cases against those accused of defaming Poland, including international media outlets.

The Law and Justice Party’s crusade to promote Poland’s heroism under Nazi occupation and end what it calls “the pedagogy of shame” attracted an international outcry three years ago, when it passed legislation outlawing discussion of Polish responsibility in the Holocaust. Leszczyńska and her backers took a different legal route in their case against Engelking and Grabowski, claiming that the historians had violated her personal rights. The court conceded that the claimant’s right to “respect for the memory of a relative” had been infringed, but threw out the other claims and did not award damages, stating that the judgment was not intended to stifle academic research. The historians are appealing the judgment.

“I’ve got real doubts about this judgment,” says lawyer Michał Jabłoński, who acted for the defence. “It is dangerous for freedom of speech and academic research. It is unprecedented that the court decides which historical source is reliable instead of researchers. This judgment requires that testimonies of survivors are verified before they are published anywhere, that researchers have to be 100% sure that testimonies are accurate before they publish conclusions, especially if they regard someone’s misconduct. In the view of the court, the existence of other sources that are contrary to a survivor’s testimony should prevent researchers from publishing their research if it interferes with someone’s personal rights. Such a standard makes historical research a dangerous job, in fact impossible, as in most cases survivors’ testimonies can’t be verified.”

International organisations and academics have also been swift to condemn the ruling. Israel’s Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem said it was “deeply disturbed by its implications.” Sascha Feuchert, director of the Arbeitsstelle Holocaustliteratur at the University of Giessen, Germany, said: “For many incidents in the Holocaust, we only have the testimonies from survivors. Of course they need to be checked and discussed in academic debates as far as possible. But this court ruling and its conclusions not only threaten the foundations of research based on survivor testimony, it could also be a gift for Holocaust deniers.”

Before the second world war, the Jewish population of Poland numbered more than three million, the largest Jewish community in Europe at the time. Just 10% survived. But Poles saved more Jews than any other country during the war, and are honoured at Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. However, Night Without End presents evidence that Poles participated in the murder of their fellow Jewish citizens on a larger scale than previously believed, estimating that two out of every three Jews who attempted to seek shelter among non-Jewish Poles died. Poland’s wartime history includes acts of barbarism alongside heroism, something that is bitterly contested by ruling powers.

Estera Siemiatycka was among the minority that survived – and it is her testimony in Night Without End for which the historians Engelking and Grabowski must now apologise. Her story is a devastating insight into the destruction of the Jewish community in Poland; Engelking has published a detailed account of her story, drawing on multiple sources, on the website of the Polish Centre for Holocaust Research, where she is director.

Siemiatycka fled the Drohiczyn ghetto in north-east Poland after it was destroyed by the Nazis and most of the inhabitants deported to Treblinka death camp. She hid in a forest with her young son, who was less than two years old, her sister and her two children, who were all captured and murdered while Siemiatycka searched for food. She then reached the village Malinowo and turned to the village elder, Edward Malinowski, for assistance. He helped her to escape Poland for Prussia, Germany, as a forced labourer.

After the war, Malinowski was brought to trial for allegedly collaborating with the Nazis and betraying a group of Jews who were in hiding. Siemiatycka gave evidence in his defence, stating that he had saved her life and helped other Jews, and he was acquitted. However, in an interview with the Shoah Foundation in 1996, under her new name Maria Wiltgren, she accused Malinowski of collaboration, and of robbing her. Engelking, who included Siemiatycka’s testimony in Night Without End, found this later testimony most reliable in reconstructing the story.

It’s a complex story, given Siemiatycka’s conflicting testimonies. However, as Engelking has pointed out, the passage in her book reports the survivor’s account; it is a matter of record. The judge stated that the historians should have limited their trust in Siemiatycka due to the discrepancies.

Ahead of Malinowski’s trial, an anti-communist gang intimidated and beat up witnesses, some of whom then changed their testimony. This could explain why Siemiatycka’s own accounts conflict. She may also, as Engelking has suggested, simply have been grateful to Malinowski for saving her life at the time of the trial.

There are fears that the courts, rather than the academic community, have become the arena for testing scholarship, and that threats against academics and journalists in Poland are becoming routine. Earlier this month, police questioned journalist Katarzyna Markusz for writing “dislike of Jews was widespread among Poles, and Polish participation in the Holocaust is a historical fact”.

Mikołaj Grynberg, a writer who has documented Polish-Jewish accounts in his books, believes that the state’s agenda to promote Polish heroism goes against historical truth. “The aim is to feel good and be a chosen people – we are the only nation that has only noble people among us,” he says. “That’s adolescent thinking and bad news that we are not growing to be an adult country. So it will stay like this for years.”

Siemiatycka’s story is just a side note in Night Without End; the focus of the book is on the fate of Jews in Poland, while Siemiatycka survived by escaping to Germany. But for the nationalists, this case is ammunition in their bid to intimidate anyone who dares to investigate the truth. In the forthcoming English translation of Night Without End, Engelking and Grabowski hope that their work will no longer make it possible to discuss Poland’s past on the basis of “sentiments, resentments or myths, but will be firmly based on sound historical knowledge”. Their case – and their appeal – are the first test.

Jo Glanville is editor of Looking for an Enemy: Eight Essays on Antisemitism, published by Short Books in May.