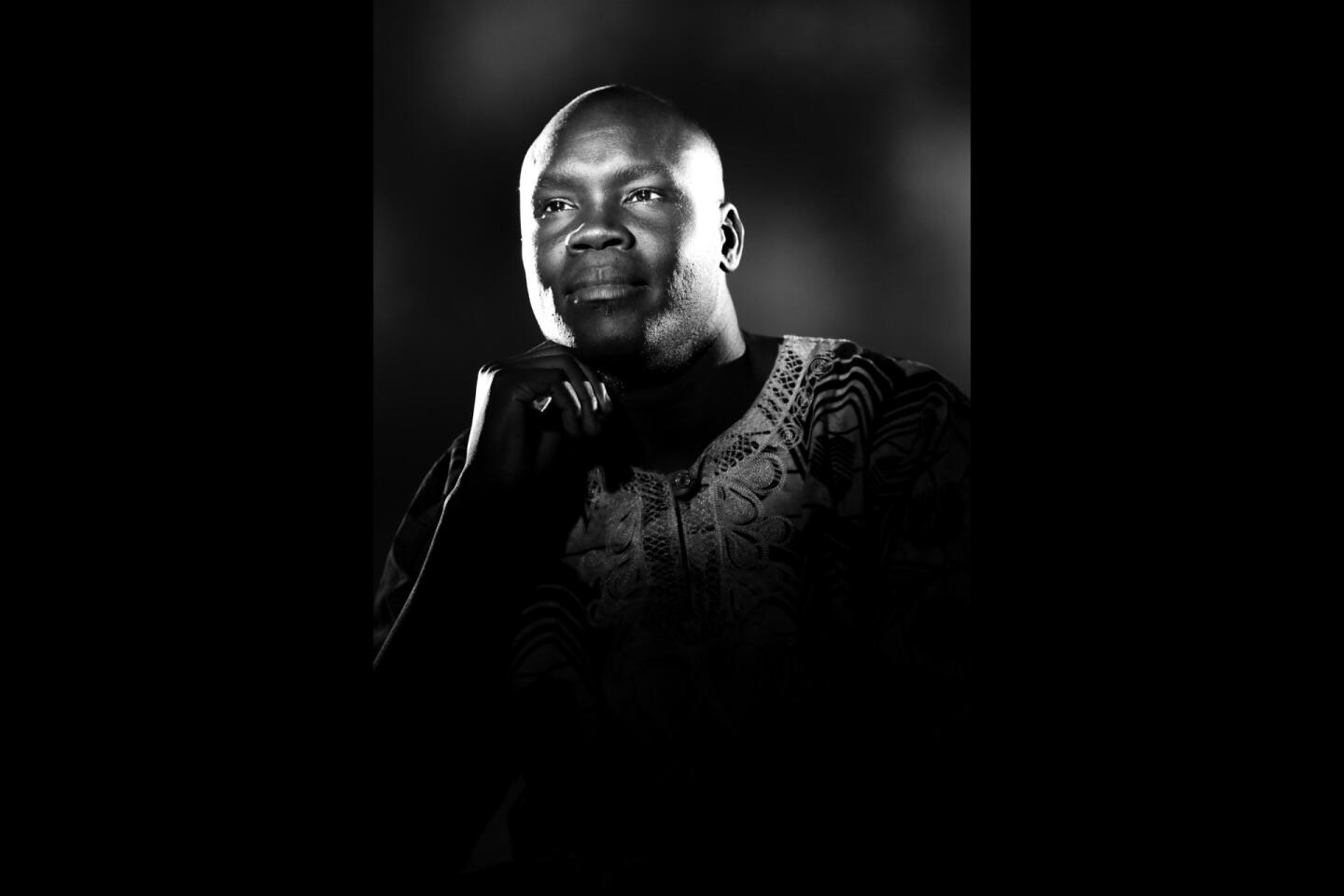

In new book, ‘Lost Boy’ Alephonsion Deng shares the story of his journey from war-torn Sudan to San Diego

For five years, Alephonsion “Alepho” Deng ran during the night with many other young Sudanese boys to evade capture. Close to starvation, he covered a thousand miles on foot — without wearing shoes or parental guidance. To survive, he had to dodge bombs and circumvent dangerous terrain filled with wild lions and crocodiles.

His journey began in 1987, when his South Sudan village of Juol was attacked. One of the now well-known lost boys of Sudan, he was forced to flee for his life. He was just 7 years old.

Deng, now 36, lived at the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya for nine years. At 19, he resettled to San Diego’s City Heights neighborhood with his older brother, Benson Deng, and a cousin, who both lived at the same camp with Deng. Their younger brother, Peter, was left behind in Kenya.

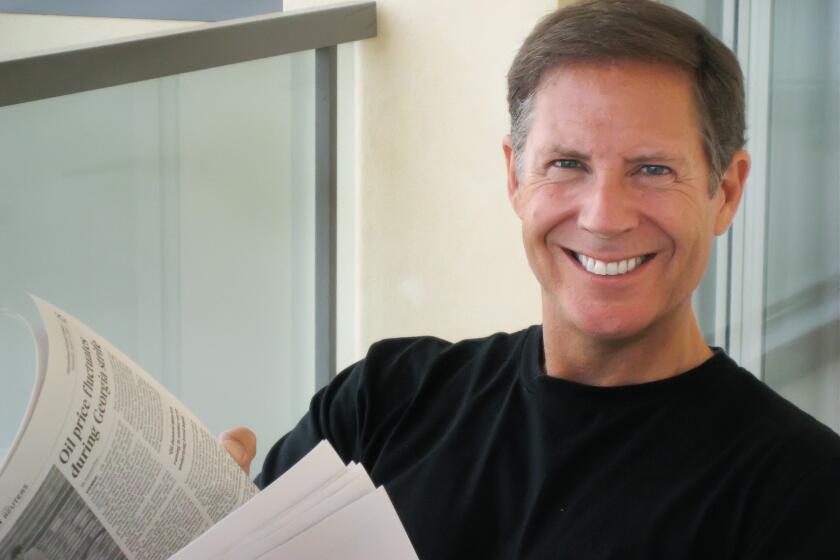

Throughout Deng’s turbulent life, writing has been a safety net. His new book, “Disturbed in Their Nests: A Journey from Sudan’s Dinkaland to San Diego’s City Heights,” is to be published in November. It portrays his harrowing experiences and his arrival to a new life in the United States. He met his co-author and mentor, Judy A. Bernstein, through San Diego’s International Rescue Committee in 2001 shortly after he arrived.

“When I was in the refugee camp, I did keep a journal of the years that I spent there. But, by the time I was ready to come to the United States, it mysteriously disappeared,” Deng said recently over a late lunch at Awash Ethiopian Market on El Cajon Boulevard. “Instead of saying ‘My Journal,’ it was ‘My Companions,’ it was my own perspective. I would write down the details, and I would take my time and really open my heart. I had never done that, and it was very therapeutic at the time.”

In San Diego during Deng’s first trip to WalMart with Bernstein, she bought him a small notepad to continue his writing. This allowed Deng to go on chronicling his new experiences and his observations.

“I thought everything was free because I saw people picking up stuff and putting it in their cart and moving around,” he recalled. “We just got here, we didn’t even have a dime, you know, not even a nickel.”

Deng recognizes that writing is an important facet of his life — and even his survival. While living in the refugee camp, he came to believe that learning English was “magic,” and could bring one out of suffering.

“I fell between two worlds,” wrote Deng, after living in San Diego a short while.

Reflecting on his past and thinking about his journaling, “Like, wow, man, never thought I would make it this far. That’s the best remedy I can have, by writing, by sharing and putting it out there.”

Between his smiles and laughter, one can see how his spirit and grit have helped him navigate life’s hardships and his destiny.

“When I arrived here (in 2001), I didn’t know how to switch on our apartment lights,” he said. “They had to send a case worker to our apartment to show us. ‘Here’s the kitchen. You serve food in the kitchen and keep food in the refrigerator. Here’s the stove and this is how it works.’ … I never operated a stove before. I was thrown into another world.”

“My accent was thick and my articulation wasn’t clear. I didn’t speak nearly as well as I do today. I was soft-spoken; I am still soft-spoken. It was hard for an American to understand me. It was a bit frustrating for me and also for them.”

Another cultural bridge for Deng to cross was eye contact. Growing up, he was taught that looking people in the eye was disrespectful. He realized misunderstandings occurred in conversation with Americans, who assumed he was being evasive.

The title of the book, “Disturbed in Their Nests,” originated from his first memoir. Published in 2015, “They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky” was written by Deng, Bernstein, brother Benson Deng and Benjamin Ajak.

“We were looking for a title, and we couldn’t find any,” Deng said with a chuckle. “ Judy liked several titles, but they weren’t catchy. One day she was looking over something I had written and there it was, that line. She saw it and said, ‘Hey, what do you think of this title?’ And I said ‘Yeah, where did you get that?’ And she showed me and said ‘You don’t remember this one?”

“There are a few reasons why I wanted to tell this story, but the main one is that everyone has a voice and you just have to find your voice. This is where my voice is right now.”

Some of Deng’s writing influences come from his favorite authors, including Chinua Achebe, Elechi Amadi, John Steinbeck and Maya Angelou.

After recently presenting a motivational speech at Southwestern College, Deng said he would like to continue giving similar talks. He has a new job at Bread and Cie Café and Bakery that he enjoys. He plans to write one more book with Bernstein and then embark on writing solo.

“I would love to go back and pursue my education. I always have a yearning to grow and to gain knowledge.”

Davidson is a freelance writer.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.